It’s been a bad week for e-cigarette haters as a new study found no evidence that e-cigarette use makes someone more likely to become a smoker. The supposed ‘gateway effect’ is a myth, except possibly in Australia where the dopey government has engineered one by banning vapes.

It has always been fairly obvious that no such gateway exists. It would be odd if vapers switched to something that is much more expensive and vastly more dangerous, and the dramatic decline in smoking rates in countries where vaping has taken off strongly suggests that e-cigarette use leads to less smoking, not more.

Meanwhile, one of the USA’s most blinkered opponent of e-cigarettes, Stanton Glantz, has drawn my attention to this study - and I’m very glad he did.

As anyone who read my first book will know, Stan’s idea of a well done study is one that confirms his priors, but this actually is a decent piece of research. It’s a randomised controlled trial that handed out e-cigarettes to a bunch of random smokers. Importantly, the smokers were not selected because they wanted to quit and they were not instructed to use the e-cigarettes, only mildly encouraged (“You are not required to use the e-cigarettes, but you might want to give them a try.”) After six months, outcomes were compared to a similar group of smokers who were not given e-cigarettes (although some of them vaped spontaneously).

Around 70% of the first group used the e-cigarettes. After six months, 14% had quit smoking entirely (compared to 8% in the control group) and 28% had reduced their cigarette consumption by at least 50% (compared to 18% in the control group). Overall, the smokers who were offered e-cigarettes were 79% more likely to quit smoking (OR = 1.79; 95% CI: 1.02–3.16). This is pretty good going when you consider that they were not particularly motivated to quit and a large number of them didn’t use the e-cigarettes at all.

But why would someone like Glantz flag up a study that ruins his anti-vaping narrative? It’s partly because he doesn’t think that giving up cigarettes is enough to make somebody a nonsmoker, as he explains in a blog post.

Because Carpenter and colleagues reported their data so completely, I could compute whether being provided e-cigarettes was associated with being nicotine free — the usual endpoint for smoking cessation studies before e-cigarettes came along — at 6 months (i.e., quitters). The picture here looks quite different: There was no significant difference in having quit (stopped using nicotine: 8% of e-cig group vs 6% of control group; p=0.510).

No, no, no. The usual endpoint for smoking cessation is not smoking. It has never been being ‘nicotine free’. People who use smokeless tobacco are not smokers. People who use nicotine patches are not smokers. People who vape exclusively are not smokers. You can’t move the goalposts just because you don’t like e-cigarettes.

As the tweet above shows, he thinks there’s something wrong with being a dual user (i.e. of vapes and cigarettes).

The results for dual use were even more interesting. At 6 months, 45% of the people who received e-cigarettes were dual users compared to just 11% of the control group (OR 6.8, 95% CI 4.2-10.9, p<0.001). In other words, for every person who stopped smoking cigarettes (including switchers who continued using e-cigarettes and quitters who did not smoke cigarettes or use e-cigarettes) in the group that were provided e-cigarettes, 2.7 smokers became dual users. This compares with 1.8 in the control group.

Being a dual user is actually fine. It is often the first step towards quitting entirely and even if it isn’t, it usually results in people smoking less (as this study shows).

The traditional objection to dual use is the idea that it maintains nicotine addiction among smokers who would otherwise have quit, but randomised controlled trials like this show that the smokers wouldn’t otherwise have quit. It is just wishful thinking.

Glantz claims that “e-cigarettes pose substantial risks” to health, but the reality-based community does not agree and the evidence does not support it. He also reckons that dual use is even more dangerous than smoking, but there isn’t really any evidence for that either. The authors of a meta-analysis he cites admit that the available evidence is very poor. (Isn’t it funny how anti-vaping academics who insist that we don’t know the long-term effects become very confident about the long-term effects when it suits them?)

Glantz also reckons that substantially reducing the number of cigarettes you smoke doesn’t have any health benefit. If true, this would make smoking unique as a health risk insofar as it the risk doesn’t increase when exposure increases. One of Austin Bradford Hill’s criteria for causation is that there should be a dose-response relationship and even Glantz admits that reducing cigarette consumption reduces lung cancer risk, which is not exactly a trivial concern for smokers.

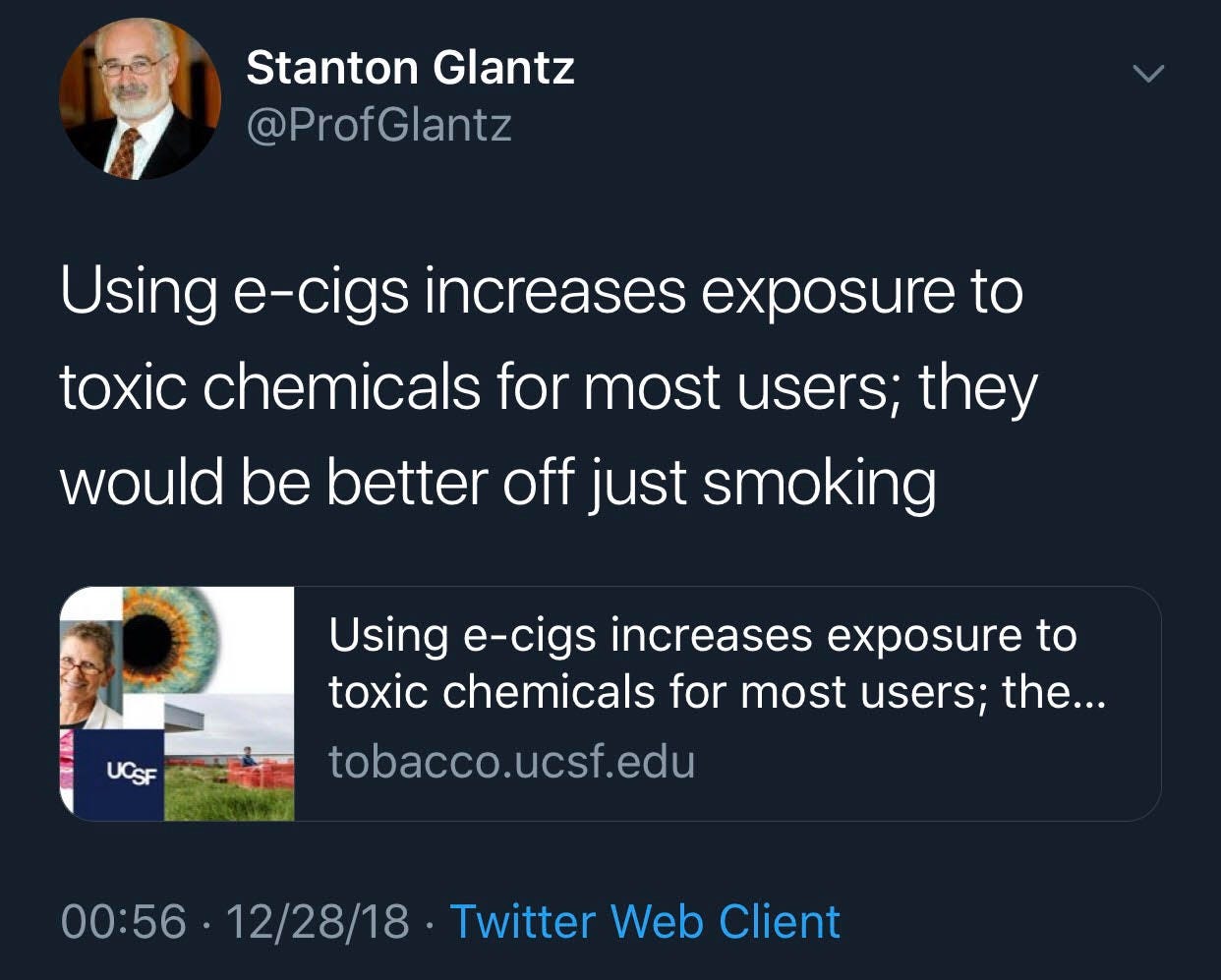

Glantz’s crusade against tobacco harm reduction must really be struggling if he has to resort to citing a randomised controlled trial that debunks most of what he’s been saying for the last decade. Still, at least he is starting to acknowledge that vaping helps people stop smoking, having previously claimed that they ‘keep people smoking’. His cranky views about the risks of e-cigarettes still need some work, but no one with any sense has taken Glantz’s opinion seriously since he advised vapers to revert to smoking anyway.

Keep up the good work Chris. These people need to be repeatedly exposed as the anti-science zealots they are.