Farewell then, Clive Everton. Along with ‘Whispering Ted’ Lowe, you bestrode the world of TV snooker commentary for decades.

The many millions of people who tuned in to hear Clive Everton’s concise and knowledgeable commentary during snooker’s golden age may not have been aware of how deeply involved in the game he was. He was not only a superb billiards player who won many amateur titles, but also a very handy snooker player who played professionally for ten years and reached number 47 in the world rankings. Not bad for a journalist. In addition to writing about snooker for several broadsheets, he founded Snooker Scene in 1972 - the year Alex Higgins won his first world title - and edited it for the next fifty years.

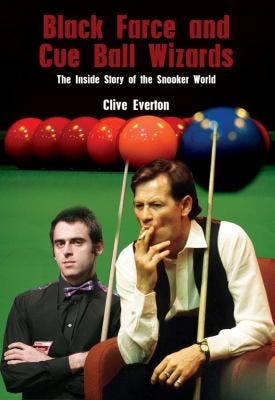

No one cared more - or knew more - about snooker than Clive Everton. Although he was a softly spoken gentleman, he had as steely a side as anyone who grew up with snooker in the mid-20th century and was never afraid to say when he felt the game was being mismanaged - which seems to have been most of the time. His idiosyncratic memoir-cum-history-cum-polemic Black Farce and Cue Ball Wizards, first published in 2007, contains many brilliant stories told with a dry wit. Here, for example is Alex Higgins being accused of using ‘gratuitously foul and abusive language’ after being beaten by Stephen Hendry in the 1991 UK Championship.

There was certainly a striking difference of recollection about what Higgins had said after Hendry had completed his 9-2 victory. Higgins remembered his remark as: “Well done, Stephen, you were a little bit lucky.” Hendry heard this as: “Up your arse, you c***.”

Snooker insiders formed their own opinions as to which of these two versions carried the greater ring of truth

But what I really love about the book is that it is a masterpiece of score-settling and grudge-holding that might as well have been called Liars and Twats. Chapter titles include ‘Greed starts to set in’, ‘Sacked by the BBC’, ‘The civil wars commence’, ‘Rotten to the core’ and ‘Sacked in a corridor’.

Most of his scorn was saved for the World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association (WPBSA), an organisation that he convincingly portrayed as a band of drunken and mildly corrupt former players who couldn’t run a bath. After becoming one of the most popular sports in Britain in the 1980s, Everton’s main thesis is that “snooker frittered away its potentialities through incompetence, mismanagement and worse.” In Everton’s account, the longstanding WPBSA chairman Rex Williams was “drunk with power or sometimes simply drunk”. His successor Geoff Foulds (father of Neal) was “driven by venality” and had a “self-righteous arrogance and boundless sense of entitlement”. WPBSA Secretary Martyn Blake is dismissed as “he of the long liquid lunches”. When Jeffrey Archer becomes non-executive president of the WPBSA and promises to “take the sport to its next stage”, Everton writes that “he certainly helped to do this, albeit in a downwardly direction”.

Black Farce and Cue Ball Wizards is a wonderfully uneven book. Everton covers the history of snooker up to 1972 in barely twenty pages, but devotes entire chapters to his personal beefs. A typical chapter (titled “Williams unleashes the dogs of war”) begins with the following sentence:

“The Williams regime’s first cowardly, underhand and petty retaliation against my critical coverage of its activities was to deprive me of my billiards membership of the WPBSA.”

Chapter 22 - titled “Foulds takes himself to the cleaners” - discusses in gleeful detail how Geoff Foulds lost a libel case against the Daily Mirror after the newspaper claimed that he had been fiddling his expenses. He even includes five pages of court transcripts. To be fair, it is a story worth dwelling on. WPBSA officials were allowed to claim £1 per mile travel expenses and this seems to have been widely abused. Foulds lived three miles from Wembley Arena where the Masters was being played and one year claimed £150 every time he attended the tournament on the improbable basis that he travelled to the venue via Colchester, waking each day at 5.30am and driving around the town looking for somewhere to set up a snooker club. On one day he claimed to have done this twice. The jury did not believe him and Foulds was bankrupted. (Bankruptcies were not unusual in snooker. Remarking on the death of former world champion John Pulman in 1998, Everton reflects that “he was twice bankrupt, first in the late ‘70s to my own disadvantage”. He had written a book with him but had never received any royalties.)

In the updated 2012 edition of the book, Everton devotes a lengthy chapter to match-fixing and more or less openly accuses several top players of cheating. Match-fixing is an undoubted problem in snooker, but what makes this chapter so joyous is Everton’s obsessive attention to detail. He spends most of it discussing an obscure match in the 2008 Northern Ireland Trophy between Peter Ebdon and Liang Wenbo which Ebdon unexpectedly lost 5-0. The match was never televised but Everton provides a series of diagrams based on the referee’s account to support his case that the match was fixed. It is gloriously nerdy stuff. (Ebdon has always denied throwing the match, but Liang was banned for life for match-fixing in 2022.)

The thing is, Clive was nearly always right. He wasn’t in it to make pots of money. He wanted nothing more than for snooker to reach as wide an audience as possible and this got him into a lot of scrapes with the WPBSA. As a player, journalist and fan, he had to walk a tightrope when dealing with officials and broadcasters, but his determination to tell the truth and call out poor behaviour always prevailed.

Everton’s obvious love of the game was undiminished and came through in his commentary. He ended the 2007 edition of Black Farce and Cue Ball Wizards by saying that the “appreciation from players and enthusiastic followers of the game far outweighs the petty enmity of those in authority demonstrating far less interest in the good of the game than in defending their own positions.”

Before adding, characteristically:

“For snooker to have survived as a public and television entertainment, considering all the mismanagement, incompetence and worse to which it has been subjected, underlines what a great game it is.”

The only people he never really forgave were the BBC. He was sacked as a commentator by the Beeb at the peak of snooker’s popularity in the mid-80s. Later reinstated, he did not miss the opportunity in Black Farce and Cue Ball Wizards to make a “needless to say I had the last laugh” aside about the man who sacked him:

“Soon afterwards, I noted, he was accepting freelance jobs as humble as directing camel racing on two cameras in Dubai.”

In 2009, after the first edition of the book was published, he was relieved of his duties as the BBC’s main snooker commentator and was soon edged out completely. (By this time, the BBC had become obsessed with having current and former champions do the commentary.) For Everton, it was the wound that would never heal. He ended the second edition of his book (in 2012) with words of conciliation towards his old foes at the WPBSA, but the BBC did not get off so lightly.

“Disagreements with the powers that be have been minor and dealt with in civilised fashion, although, on the other hand, I will forever resent my BBC career ending with scant courtesy shown to me”.

RIP Clive.

Quite an obituary. He was an excellent commentary.

I wonder how common it is for a sport’s administrators to become disconnected from the thrill of whatever it is they’re meant to be showcasing. It’s like a form of regulatory capture - so busy defending their fiefdoms they forget what they got into it for. I suspect it’s rather more widespread than one would like, which then raises the question of how you’d identify it.

And Everton sounds an absolute nightmare for those who are bogged down in that sort of thinking.