Further to my post on Friday and my paper on Thursday, the “tobacco playbook” has appeared in the Sunday Times. Don’t worry, you won’t get an e-mail every time this happens, but it is a classic example.

In October, the UK will introduce the most extensive restrictions on food advertising anywhere in the world. Ads for ‘less healthy’ food will be banned entirely on the internet and before 9pm on television. This is a huge political victory for the likes of Jamie Oliver and the Obesity Health Alliance who have been campaigning for such a ban for years.

The downside of this, from their perspective, is that everybody will see that it doesn’t work. And so they are getting their excuses in early. Their new narrative is that the ban doesn’t go far enough because of ‘loopholes’ and that these ‘loopholes’ exist because of food industry lobbying. Cue the “tobacco playbook”…

From October in the UK, marketing of foods high in fat, salt and sugar will be banned in paid online promotions and shown on television only after 9pm. But experts say loopholes remain in the form of unpaid online promotions, brand-only marketing and outdoor advertising.

Katharine Jenner, director of Obesity Health Alliance, a coalition of more than 60 health organisations, said years of delays, fuelled by consultations and industry pushback, had drained momentum in Britain. “It’s a tobacco [industry] playbook tactic — delay, deny and dilute. They hope to kick the can down the road by getting in as many loopholes as possible, while disputing clear evidence that policies like this work,” she added.

One gets the impression that Katherine Jenner has a piece of string hanging out of her back. Pull it and she recites one of three clichés (in her previous life as a lobbyist for Action on Sugar, she would robotically declare herself “shocked” by any amount of sugar in any food product). She used almost exactly the same words in the British Medical Journal recently, as I mentioned in The Critic on Friday.

“It’s quite a well proven tobacco playbook strategy,” she says. “What the companies try to do is deny and undermine the evidence, to say it’s not important; they try to delay policies coming in; and, they dilute them as well, make them as least impactful as possible.”

This is gaslighting. The food industry has been comprehensively defeated by a handful of fanatics. Food companies have failed to fight their corner and it wouldn’t surprise me if some of the bigger brands welcome the advertising ban as a way of keeping out the opposition. There has been no public-facing campaign against any of this and insofar as there has been lobbying in private, it has been useless.

Jenner wants us to believe that the food industry has won (by consulting the infamous playbook) because the ban doesn’t include “unpaid online promotions, brand-only marketing and outdoor advertising”. Aside from the fact that it would be insane to prosecute private individuals for tweeting “I love Big Macs” - which is what a ban on unpaid online promotions would involve - these are not “loopholes” by any reasonable definition. If the government had wanted to ban these things, it would have said so. They were never part of the legislation and even the likes of Jenner were not demanding them until about five minutes ago.

In 2017, the Obesity Health Alliance put out a little report which said:

To protect our children from adverts that we know can influence their food preferences, choices, and consumption, the Government should extend existing regulations to restrict HFSS advertising where children are exposed to the most HFSS advertising. The most effective way to do this would be with a 9pm watershed.

There was nothing in this document about outdoor advertising or “brand-only marketing”.

In 2019, they put out a press release calling for a ban on ‘junk food’ advertising in “all types of media”. They didn’t define ‘junk food’ (they never do), but they did define what they meant by “all types of media”. They meant TV, radio and online. The only mention of outdoor advertising was digital outdoor advertising.

In a press release titled ‘Protect children from all junk food advertising’, OHA explicitly defined what they meant by “all”.

The OHA wants to see a 9pm watershed on junk food adverts implemented across all media devices and channels to protect children from the harmful effects of marketing of foods high in fat, sugar and salt. This 9pm watershed should include live TV, TV on demand, radio, all types of online, social media, apps, in-game, cinema and digital outdoor advertising such as billboards.

If the Obesity Health Alliance had wanted the ban to extend to newspapers, magazines and conventional billboards, this would have been the time to mention it. They didn’t, because neo-prohibitionists always use the tactics of the salami slicer: one chunk at a time. (To this day, they are cagey about mentioning newspapers because they need the support of journalists, but their time will come.)

Jenner is gaslighting you into thinking that they have always campaigned for a total ban on ‘junk food’ advertising and that the only reason this hasn’t happened is because the food industry has been using the mythical “tobacco playbook”. The Sunday Times is only too happy to further this narrative, claiming that the government “seems to be appeasing the food industry”.

While that commitment remains to be seen, Latin America has shown what’s possible when public health comes before politics. Can Britain muster up the courage to go even further from October?

The theme of the article is that Chile has successfully used regulation to tackle obesity (the headline is ‘If Chile can stop children eating junk food, why can’t Britain?’). Chile is one of the few countries to have major restrictions on food advertising. It banned ‘junk food’ advertising during TV programmes aimed at under-14 year olds in 2016 and then, in 2018, banned it completely before 10pm. The UK banned such advertising during programmes aimed at under-16s back in 2008 and the forthcoming ban is more extensive than Chile’s because it includes all online advertising.

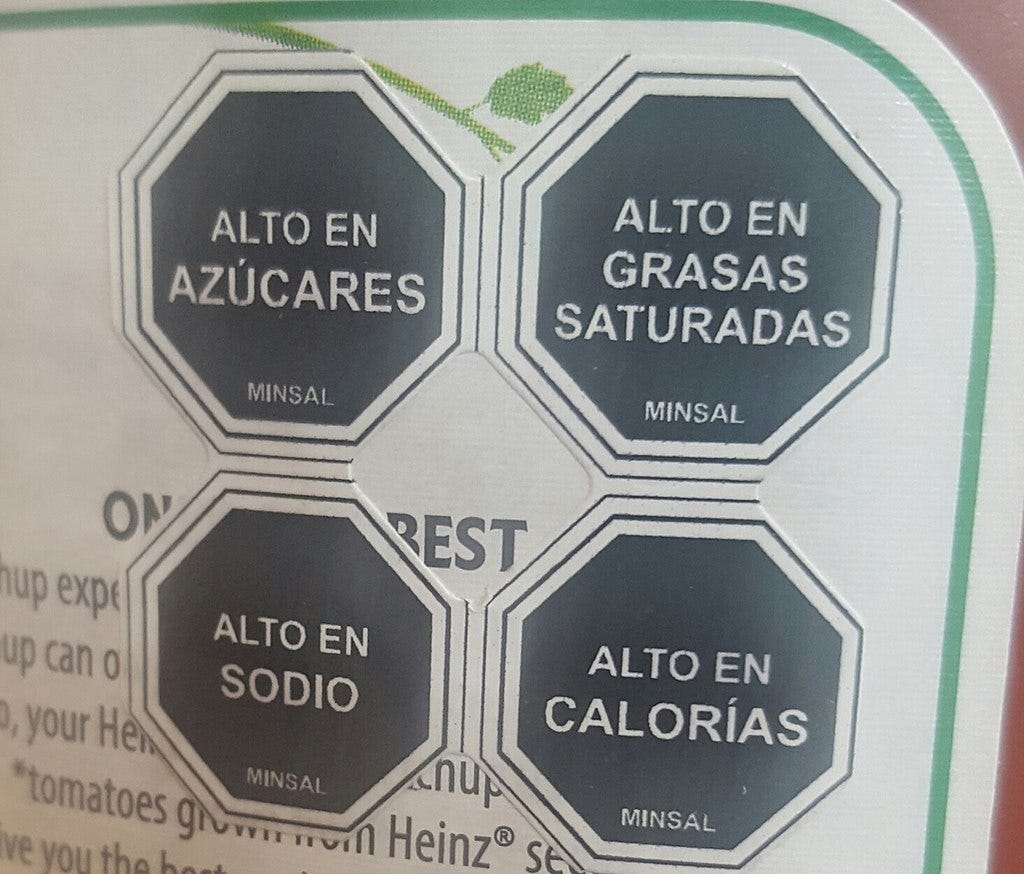

Nanny statists like Chile because it has banned cartoon mascots such as Tony the Tiger from being used on packaging and because it uses black octagons to warn about high sugar/salt/fat content rather than the red traffic lights used in Britain. For some reason, this is supposed to be a gamechanger.

To show that Chile’s advertising ban has worked, the article includes the graph below, with data copied from Our World In Data which has used figures from the WHO. The veracity of this data is highly questionable. The figures for the UK bear no resemblance to the figures from the National Child Measurement Programme and the figures for Chile are derived from a model, not a survey. The confidence intervals are also enormous. The most recent figure of 8.8% has a confidence interval (ie. margin of error) of 6.1% to 13.0%. In 2017 - the year before the advertising ban took effect - the rate was 9.2% (7.0%-11.9%) so there has been virtually no decline since even if you trust these modelled numbers.

A study published last year found no change in rates of overweight or obesity among Chilean children of any age between 2016 and 2019. According to the Chilean government, the rate of child obesity rose from 16% in 2009 to more than 26% in 2022.

This is the kind of ‘success’ the UK can look forward to.