Liz Truss didn’t break the economy. It was like that when she found it.

Hair of the dog economics has failed.

I knew for certain that the economy was doomed in June 2020 when lockdown was extended for yet another three weeks. It wasn’t the amount of money the government was borrowing that alarmed me as much as the insouciant way in which it was being borrowed and the apparent apathy of the majority of people towards it. Far from being concerned about the size of the national debt, les bien-pensants argued that the government’s ability to borrow so much during Covid - ultimately £375 billion - proved that it had been miserly to borrow so little since 2010. The Covid splurge proved that ‘austerity’ was a ‘political choice’.

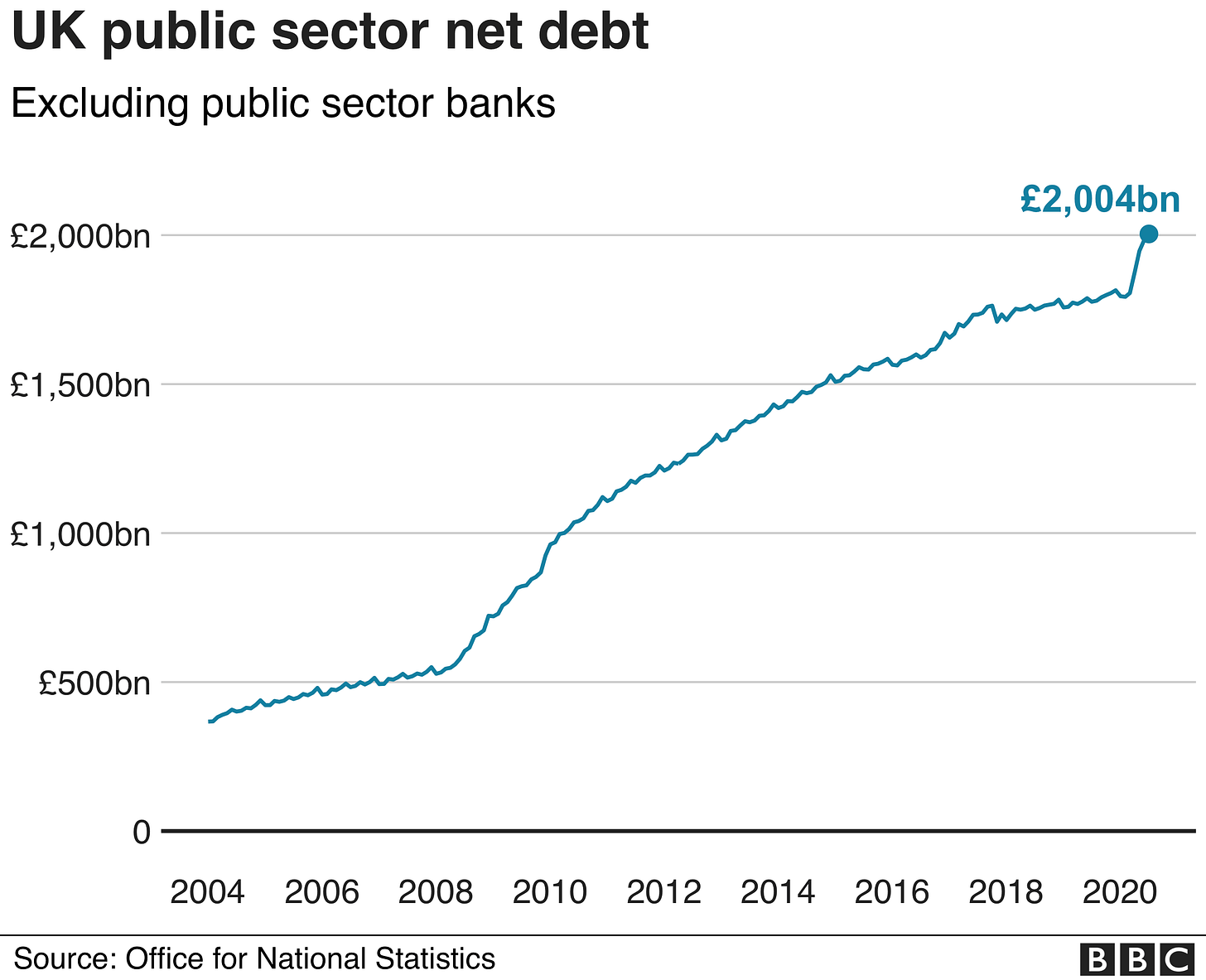

I find it staggering that anyone can look back at the last fifteen years and conclude that the problem with the UK was that it didn’t borrow enough money. Between 2010 and 2019, we borrowed about £750 billion, of which half was created by the Bank of England through QE. Since 2001, we had borrowed £1.4 trillion.

Long before the pandemic began, I was troubled by emergency economic policies - ultra-low interest rates and money printing - being in place for a decade without any emergency to justify them. This led to a great deal of inflation, but since the inflation had mainly affected the housing market and stock exchange and had made the rich richer, it didn’t seem to count. Then, in 2020, we had an actual emergency which seemed likely to push us over the edge.

Regardless of whether we were in lockdown or not, the pandemic would have required a huge amount of spending, but extending lockdowns beyond what was required to ‘protect the NHS’ exacerbated a precarious financial situation. Pointless money-pits like Eat Out to Help Out only served to show that the government treated borrowed cash like confetti.

It seemed to me that the economy was a house of cards that would be toppled by the first sign of inflation. And yet, in mid-2020, the idea that gorging on vast quantities on newly printed money, combined with the near-global shutdown of important industries, would lead to inflation was considered eccentric and would remain so for at least another year (although not at the IEA).

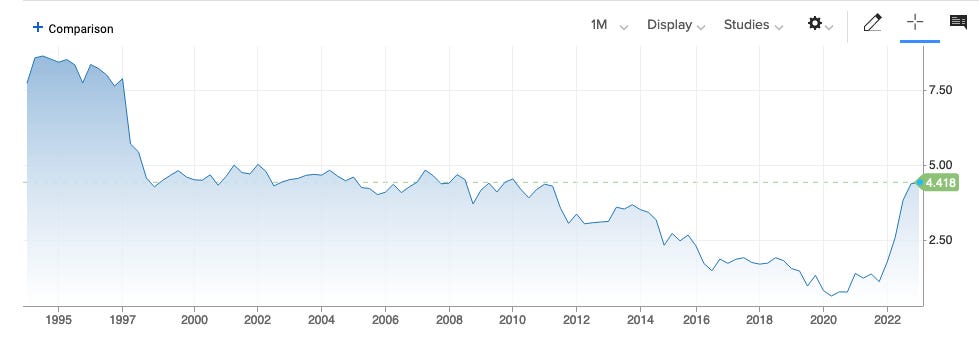

Retail prices had been suppressed for so long that a whole generation couldn’t remember inflation. Central bankers had convinced themselves that they had beaten it. And since central bankers had decided that interest rates only existed to control prices, a lot of people had forgotten about high interest rates too. A thirty year old who took out a mortgage in 2022 would have been a child the last time interest rates were at normal levels and wouldn’t even have been born the last time inflation exceeded six per cent.

Skip forward to late 2021 and the inevitable had happened.

In January 2022, a month before Russia invaded Ukraine, inflation was running at 5.5 per cent in the UK, 5.1 per cent in the EU and 7.5 per cent in the USA.

Eight months earlier, the Bank of England had predicted a ‘temporary’ rise in inflation that would peak at 2.5 per cent in Q4 of 2021. With that forecast in tatters, it now leapt into action by raising interest rates to, er, 0.5%. Unsurprisingly, this didn’t have much effect. In May 2022, when inflation hit 9.1 per cent, the BoE raised interest rates to the dizzy heights of one per cent and told people to not ask for a pay rise. This, too, failed to achieve very much.

By September, as we now know, inflation was at 10.1 per cent. The pound had fallen from $1.37 to $1.13 since the start of the year. 30 year gilt yields had risen from 1 per cent to 3.5 per cent. A recession, or something very close to it, had already begun. Interest rates rose to 2.25 per cent and it was a question of when, not if, they would rise again.

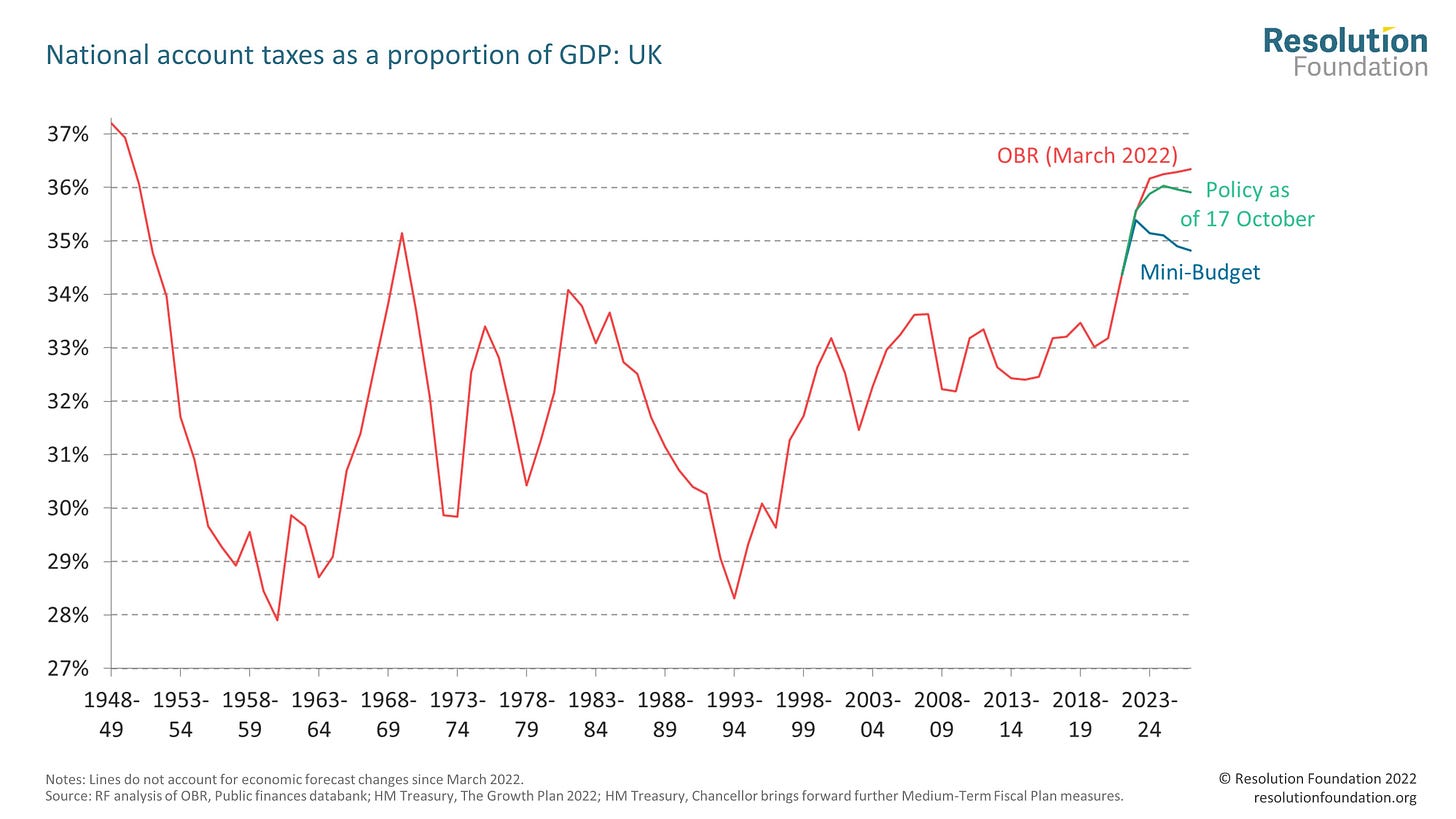

This was the backdrop to the ‘mini-budget’ of 23 September, the cornerstone of which was a colossally expensive, but strangely uncontroversial, energy price cap. On top of this largesse, the Chancellor added cuts to income tax, National Insurance and stamp duty and froze Corporation Tax. It was a sign that Britain was under new management. If people didn’t want spending cuts or higher taxes, there was only one course of action: the single-minded pursuit of economic growth.

But, as I said at the time, tax cuts alone were not going to generate 2.5 per cent growth and the largest ‘tax cut’ (to Corporation Tax) wasn’t even a cut. The mini-budget was supposed to be followed by a series of supply side reforms. We waited and waited, but nothing came. To my knowledge, not a single piece of deregulation has been announced, let alone introduced, aside from lifting the ban on fracking (which will probably not happen because of an anti-growth coalition of Tory MPs).

Some saw the mini-budget as an invitation to the Bank of England to raise interest rates. If so, it was an invitation that was declined. Some thought the mini-budget implied that there would be spending cuts, but Liz Truss insisted that there would be none. Instead, Kwasi Kwarteng took to the airwaves to announce that he intended to make more unfunded tax cuts.

Previous governments had at least paid lip service to balancing the books. The Truss administration didn’t even bother pretending. The bond markets, seeing no plan for growth and no sign of an interest rate rise, naturally demanded a greater return on their investment. 30 year yields nudged toward 5 per cent. The pound fell to a low of $1.07. Pension funds that had been making what the Economist describes as ‘obscure derivatives bets’ found themselves short of liquidity thanks to higher gilt yields - although they insisted that they were not short of capital - and so the Bank of England stepped in to lower yields by buying gilts.

The rest is history. With the opinion polls suggesting a total wipe out at the next election, the Conservative Party’s men in grey suits intervened, elbowing Truss out of the way and pushing Jeremy Hunt in front of the cameras to deliver an almost total U-turn.

So ended the dash for growth, nipped in the bud before it delivered any pro-growth policies. Matt Hancock has called it ‘libertarian economics’. Various people have self-serving reasons to portray it as such, but it was nothing of the sort. It was more like a kind of right-wing Keynesianism, seeking to stimulate spending by borrowing money to cut taxes.

Liz Truss was dealt a bad hand and played it badly, but despite the broadcast media spending a fortnight treating every day as if it were Black Wednesday, she did not ‘crash the economy’, as the Labour Party has claimed. The economy was already in pieces and there is much worse to come. Goldman Sachs has already taken 0.6 per cent off the UK’s GDP forecast for 2023, partly because of the rise in Corporation Tax. There is nothing to celebrate about the return of an ‘orthodoxy’ that has brought us an insane housing market, negative real interest rates, double digit inflation, taxes at a 70 year high, exponential spending on the worst health service in Europe, £2.4 trillion of debt and lower wages than we had in 2008.

There are two obvious lessons from the house of cards falling down but we are in danger of not learning (or re-learning) them.

Firstly, printing too much money creates inflation. Duh.

Secondly, interest rates have existed for thousands of years for good reason. They are, to quote the title of Edward Chancellor’s excellent book, the price of time. Or, if you prefer, the cost of impatience. They should provide an acceptable return to lenders and should certainly be above the rate of inflation. The international experiment with very low interest rates has, unsurprisingly, led to governments, businesses and individuals becoming heavily indebted. As people take on more debt, they become increasingly vulnerable to interest rate rises. This leads to a doom loop in which central bankers are reluctant to tackle inflation because interest rate hikes will make people poorer and so inflation persists, making people poorer.

Even in the absence of inflation, interest rates couldn’t be raised because it would ‘wreck the recovery’. An economic recovery so feeble that it cannot withstand an interest rate of one or two per cent barely deserves the name. The economy had become like an alcoholic. Every drop in interest rates and every bout of money-printing made it feel better in the short-term, but they made the addiction worse and was slowly killing it. It was hair of the dog economics.

It seems inconceivable that we will walk away from this economic crisis without learning these lessons but you can already see the seeds of an alternative narrative taking root: that everything was fine until Russia turned off the gas and Liz Truss tanked the economy.

It is theoretically possible that the government, under Truss or someone else, will make a dash for growth through deregulation, but it seems vanishingly unlikely. The vested interests are too strong for a weak government to take on and the benefits would take too long to be realised for it to be politically worthwhile. Managed decline and secular stagnation are all that is left.

The only difference is that everyone is now a fiscal conservative. This is Liz Truss’s accidental gift to the nation. She has unwittingly shown that austerity was not a ‘political choice’. She has shown that the government cannot endlessly borrow money at low rates without having a plan to pay it back, or at least scale it down. If gilt yields rising above 4 per cent (which is not high by pre-orthodoxy standards) is a national emergency, the era of big borrowing is over.

The left have already started wailing about ‘Austerity Mark 2’, but they are now going to have start telling us which taxes they want to increase to pay for their spending priorities. They may find that they get a rough reception. It is notable that almost the only thing left from the mini-budget is the scrapping of the Health and Social Care Levy. Even Labour didn’t want to keep it. It’s unpopular. Fine. But if you can’t get the public to support a tax specifically earmarked for the NHS - the one thing that normies say they are happy to pay more tax for! - good luck raising taxes for Net Zero and foreign aid.

We will probably see the worst of inflation this winter. Wage settlements have generally been below the rate of inflation and gas prices are falling. But the hopes that inflation will be ‘transitory’ have withered. There is already talk of central banks raising their (apparently pointless) inflation targets to 4 per cent. Interest rates and bond yields are going to rise further, possibly much further. Zombie companies and people who were daft enough to mortgage themselves up to the eyeballs will suffer. Savers will benefit but no one cares about them. In an economy built around debt, the prudent are suckers.

Those who lose out from higher interest rates will say that the Bank of England could have chosen to keep rates low. The MMT loonies will say that the recession could have been avoided if the Bank hosed us down with one more burst of QE. Everything looks like a ‘political choice’ if you ignore trade-offs and consequences, but the number of practical options available have narrowed considerably. As Janan Ganesh says in the FT today, Labour are not going to enjoy governing without a magic money tree to shake.

Hair of the dog economics has had its day. The era of big borrowing has come to an end. We have run out of road. It would be unfortunate if Liz Truss has given economic growth a bad name because it really is our only way out of the woods.

A different and shorter version of this was published in the Daily Mail.

I agree with a lot of your article, I especilly like "There is nothing to celebrate about the return of an ‘orthodoxy’ that has brought us an insane housing market, negative real interest rates, double digit inflation, taxes at a 70 year high, exponential spending on the worst health service in Europe, £2.4 trillion of debt and lower wages than we had in 2008." But the worm has turned if my memory serves me correctly. I seem to remember you advocating lockdowns as the best thing since sliced bread. Apologies if my memory is wrong, but i'm sure I wanted to throw something at the TV listening to you saying how necessary they were? As has been shown, but was know at the time lockdowns were never either necessary nor sensible. And yes the economy would have taken a slight hit as they do in pandemics but not nearly as bad if the government had stuck to normal pandemic planning, ie, not terrify the population and keep everything on an even as footing as possible. That is what happened in the two pandemics in 50/60s. And the economy fell a bit then but recovered, and the Swedish economy has not suffered nearly as much as ours, because they used a standard pandemic playbook and not the Chinese version which was designed to destroy our economy. But with Jeremy Hunt's links to the CCP he'll finish what was started no doubt.

Brilliant.

A concise summary of what has been going on for the last decade or so reaching its inevitable conclusion. To a non-economist most of it is just common sense and obvious but apparently not to decision makers.

It still staggers me that in our whole history to 2008 we had built up a debt of about £600bn but in the space of just 14 years since we have more than trebled that.