Some new ‘public health’ science just dropped in Australia. A team of eleven researchers set up a 10 minute online test for 15-17 year olds looking at their responses to pictures of alcohol-free drinks.

Low- and no-alcohol beverages are a current obsession of the neo-temperance lobby because they are an industry-led innovation (see Not Invented Here). Cue the usual ‘gateway effect’ and ‘normalisation’ bollocks.

Some of their concerns are about what they call ‘alibi marketing’, i.e. manufacturers advertising a zero-alcohol variant of a well-known brand with the covert intention of getting people to buy the alcoholic version. They don’t seem to understand that if you want people who drink Guinness to try something that tastes very much like Guinness, it is helpful to call it Guinness 0.0 rather than give it a completely new name that doesn’t mean anything to anybody.

In any case, it turns out that they disapprove of zero-alcohol drinks even when they’re not trading off the back of a well-known brand.

Other zero-alcohol drinks feature “new-to-world” (NTW) brands – that is, products that feature brands unique to zero-alcohol drinks - but are packaged and labelled similarly to alcoholic drinks. Both types of zero-alcohol drinks thus look visually similar to alcoholic drinks, especially in retail or advertising environments.

Er, OK.

Yet, these drinks often do not meet regulatory definitions of “alcohol”, for example due to their very low-to-no alcohol content and lack of definition within alcohol regulations; indeed, zero-alcohol drinks may fall within the remit of food and soft drink, rather than alcohol, regulations.

The term ‘regulatory definition’ implies that there is some other kind of definition that would include non-alcoholic drinks as alcohol. They are literally called ‘zero-alcohol drinks’. How much clearer can it be that they are not alcohol products?

Given the strong visual resemblance between zero-alcohol and alcoholic drinks, it is plausible that exposure to zero-alcohol drinks functions similarly to exposure to alcoholic drinks. That is, exposure to zero-alcohol drinks may increase people’s desire to try, or act as a reminder to consume alcohol.

Or it might increase people’s desire to try the drinks that are being advertised! That is generally the point of advertising. There are a lot of new products being launched in the growing market for low- and no-alcohol drinks at the moment, and people won’t buy them unless they know that they exist. Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

And if people drink zero-alcohol drinks instead of alcoholic drinks, they will consume less alcohol, which is presumably what these academics want. Whether this happens in practice is a question that can be answered through empirical research and the answer is yes, that is exactly what happens.

These researchers don’t intend to test that particular hypothesis, however. They have something much more basic in mind. They recruited a bunch of teenagers to do a brief online survey in which they were shown photos of things and asked simple, leading questions.

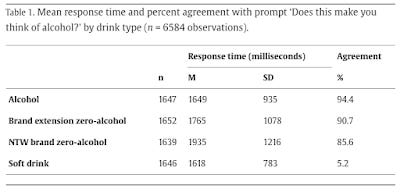

First, participants were shown five practice images of either dogs or cats, and asked to respond as quickly as possible to the question “Is this a dog?” (response options: “Yes”/“No”). After the five practice images, participants were then advised that they would be shown a series of images of different drink products, and asked to respond as quickly as possible to the question “Does this make you think of alcohol?” (response options: “Yes”/“No”). Participants were then shown the 20 stimuli in randomised order.

They were then shown photos of alcoholic drinks, low- and no-alcoholic drinks, and traditional soft drinks. To the surprise of no one, when given the unsubtle prompt of being asked “Does this make you think of alcohol?” a large majority of the youngsters said ‘yes’ when they were shown photos of products that look like alcoholic drinks and an equally large majority said ‘no’ when they were shown photos of products that look like traditional soft drinks.

If you’re expecting the next stage of the study to involve ascertaining whether any of this led to the participants drinking alcohol, you’ll be disappointed because that’s where the study ends. Despite their hypothesis being that “exposure to zero-alcohol drinks may increase people’s desire to try, or act as a reminder to consume alcohol”, the authors don’t bother trying to find out. But that doesn’t stop them writing a “policy implications” section (always a red flag that you’re reading activism masquerading as academia).

These findings have important implications for policymakers, as they indicate a need to regulate the advertising of zero-alcohol drinks in a similar manner to alcoholic drinks to limit children’s exposure to these drinks and their advertising.

In some countries - but not Australia - that would mean a complete ban. That seems a bit of an over-reaction when the only evidence presented is that when 15-17 year olds are shown bottles of non-alcoholic wine and non-alcoholic beer, they think of the word ‘alcohol’ when someone says the word ‘alcohol’ to them. It also seems counter-productive from a ‘public health’ perspective since these products are substitutes for alcohol, but let’s face it, it’s never really been about health, has it?

It is almost as if the researchers had the conclusion in mind before they started the study.

And I’ll say it again: it took eleven academics to produce this.

Thanks for sharing a bit about the methodology.

Nearly a half century ago, Paul Rozin showed that if you label a substance as "not poison", people grow wary of it anyway. Because they're thinking of poison now.

So of course seeing a product labeled as "non-alcoholic" makes people think of alcohol. How could they not?

Which is to say that maybe the study design is a priori worthless, to put it harshly.

The researchers are on a completely wrong track if the think big-beer are cynically marketing low and no alcohol products to promote consumption of their alcoholic twin.

Assuming the production process hasn’t changed, when I was involved in the process the brewery brewed their standard fare in the standard way, at standard cost. They then removed the alcohol, claimed the tax back on the alcohol that had been removed, sold it for medical purposes (tax-free), and then sold the low/no alcohol stuff for the same price as the standard fare. Genius!