Sugar tax was not a total flop, sugar tax advocates claim

'Public health' academics apply lipstick to a pig

Just before Britain’s sugar tax was introduced in April 2018, various advocates of the policy were handed £1.5 million of taxpayers’ money to evaluate it. Marking your own homework is considered perfectly normal in ‘public health’.

They had their work cut out because what the government classifies as child obesity (but actually isn’t) rose in 2018/19, rose again in 2019/20 and then rose dramatically in 2020/21; the latter doubtless being lockdown-related.

Clearly unable to claim that childhood obesity declined after the tax was introduced, the evaluation team settled for arguing that there was less sugar in soft drinks as a result of the tax.

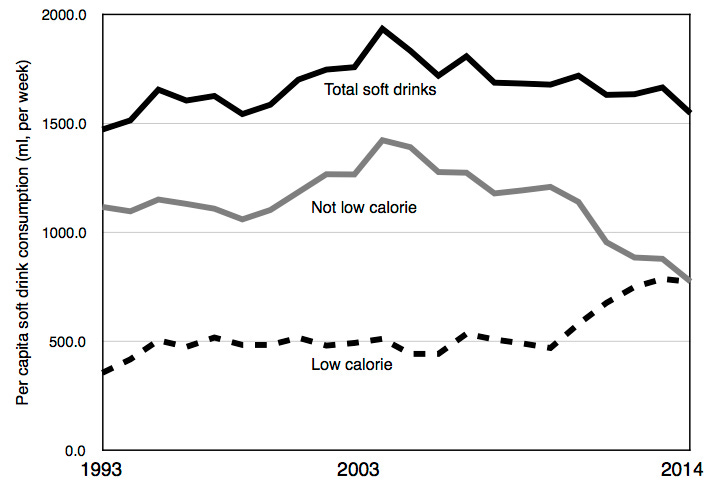

On average, this is probably true, although much depends on how much you trust the counter-factuals above. The effect certainly wasn’t very large and sugar consumption from soft drinks had been dropping for many years anyway.

Since soft drinks only provide around 2% of the nation’s calories and there had been no decline in obesity in previous years when sugar consumption from soft drinks had been in freefall, it was unlikely that the sugar tax would have any measurable impact on obesity rates. This seemed to be confirmed by obesity rates for both children and adults being higher in every year since the tax was implemented.

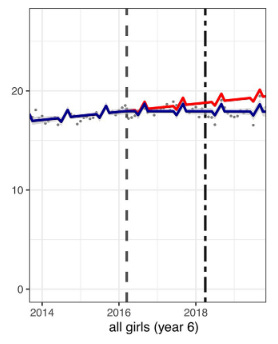

Today, however, the evaluation team is claiming victory based on an extremely sketchy model. They created a counterfactual based on trends between 2013 and 2016 and then compared it to what actually happened. Child obesity didn’t actually decline among any groups. Even relative to the counterfactual, it didn’t decline among boys of reception age or girls of reception age. It didn’t decline among Year 6 boys either. But there was, supposedly, a 8% decline among Year 6 girls. This, again, was only a relative decline. Even among this subgroup of the population, rates of obesity actually rose.

Even the strongest association of the SDIL [Soft Drinks Industry Levy] among the most levy-responsive groups (e.g., year 6 girls) reflected only a dampening of the rate of increase in obesity prevalence compared to the counterfactual rather than a reversal in trends.

When the researchers produced a counterfactual based on data from 2013 to 2018 - when the tax was actually implemented - it found that obesity was higher than expected among reception age kids and about the same as expected among Year 6 kids. This finding is filed away in the supplementary material and the authors barely mention it.

The authors conclude that…

Our results suggest that the SDIL was associated with decreased prevalence of obesity in year 6 girls, with the greatest differences in those living in the most deprived areas.

And, inevitably…

Additional strategies beyond SSB taxation will be needed to reduce obesity prevalence overall, and particularly in older boys and younger children.

This study will doubtless be cited as evidence that the sugar tax ‘worked’, but it is extremely thin gruel. Apart from requiring some very obvious cherry-picking to find evidence of success, it requires us to believe that the mere announcement of the sugar in 2016 reduced obesity among one very specific demographic, while the introduction of the sugar tax did not.

The authors argue that the announcement of the sugar tax incentivised soft drink companies to reformulate their drinks. Indeed it did, but not straight away and not in huge numbers. Lucozade and Ribena took the sugar out in 2017 and Irn-Bru halved the sugar content in 2018. It seems unlikely that this would be enough to reduce obesity among 10-11 year old girls by 8%, especially since it mysteriously had no effect on anyone else.

The counterfactual for those girls is shown below in red. The real obesity figures are shown in blue. You can see that the trend in obesity was essentially flat from 2015 to 2018 - i.e. before the sugar tax - but the counterfactual keeps on rising. Voila! The gap between the two lines is your 8% reduction in obesity. The evidence for the sugar tax being even a partial success starts and ends with this chart.

Even if you have faith in the highly suspect counterfactual scenario, why on earth would the sugar tax drive a significant reduction in obesity among Year 6 girls but not Year 6 boys? The authors confess themselves to be baffled...

‘it is unclear why this might be the case, especially since boys were higher baseline consumers of SSBs [sugar sweetened beverages]’

So they take the opportunity to splutter something about their current policy objective, advertising bans.

One explanation is that there were factors (e.g., in food advertising and marketing) at work around the time of the announcement and implementation of the levy that worked against any associations of the SDIL among boys.

There is no evidence for this whatsoever.

And why would Year 6 children be affected and not reception age children? Apparently, it was never likely to benefit younger children…

This result is congruous with findings from a cohort of British children showing that SSB consumption at ages 5 or 7 are not related to adiposity at age 9 years

Now they tell us! I don’t remember Jamie Oliver saying that, do you?

The lack of impact on young children gives the authors an excuse to once again push for more action from government…

Fruit juices, which are not included in the levy, are thought to contribute similar amounts of sugar in young children’s diets as SSBs and may explain why the levy alone is not sufficient to reduce weight-related outcomes in reception age children. In addition to drinks, confectionery, biscuits, desserts, and cakes are also important high-added sugar items, which are regularly consumed by young children and could be a target of additional obesity reduction strategies.

With the case for sugary drink taxes now ‘proven’ in the fairytale world of ‘public health’ academia, taxes on ‘confectionery, biscuits, desserts, and cakes’ will no doubt be next. And when those taxes also patently fail to reduce obesity, we can expect a lavishly funded evaluation team to turn up wielding the carefully selected findings from another dodgy model to prove that those, too, have been a triumph.

To date, the sugar tax has cost consumers well over a billion pounds.