Alcohol and Mendelian randomisation

What if the Emperor has no clothes?

In Mendelian randomisation (MR) studies, researchers look at genetic variants that are associated with specific traits, conditions and behaviours to test whether those traits, conditions and behaviours and associated with certain outcomes. Since the genes are distributed randomly throughout the population, the idea is that the researcher can avoid confounding factors such as poverty, diet and age and establish causality. For example, people with genes associated with higher levels of “bad” cholesterol have been found to have greater risk of coronary heart disease and lower life expectancy, thereby confirming the findings of observational epidemiology.

But MR studies have also challenged some findings from observational epidemiology. Many epidemiological studies have found that moderate drinkers have lower rates of stroke, heart disease and overall mortality than teetotallers and heavy drinkers. This association is robust when all conceivable confounding factors are controlled for and when ex-drinkers are excluded. Since moderate drinking demonstrably lowers “bad” cholesterol, this should not be surprising but it has always been contentious among many “public health” academics/activists because they prefer the simpler message that alcohol is bad for you.

In recent years, several MR studies have found no relationship between genetically predicted moderate drinking and better health outcomes. These studies have been widely reported and temperance-adjacent academics have argued that they trump the rest of the evidence. The problem is that there is no gene for moderate drinking.1 In its absence, some researchers have turned to genetic variants such as alcohol dehydrogenase (ALD) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) which give people unpleasant sensations (flushing, nausea, etc.) when they drink alcohol. This discourages heavy alcohol consumption, but it also discourages alcohol consumption in general. It is therefore a poor proxy for moderate drinking. Moreover, although the ALDH2 variant is relatively common in East Asia, it is fairly rare in the rest of the world (8% of the world’s population have it) and it does not just cause mild unpleasant symptoms. It is also associated with an “increased risk of alcohol-related diseases, including cancer and heart disease, even at lower levels of alcohol consumption”.

If scientists said that moderate drinking reduces mortality risk for most people, but raises the risk for a subset of people with unusual genes, that would be fair enough. But instead, some MR researchers have assumed that people who are basically allergic to alcohol are moderate drinkers and, when these people show no benefits - and sometimes harm - from drinking (or rather from “genotype-predicted mean alcohol intake”), they declare that moderate drinking is bad for everyone’s health. The most influential of these studies was published with great fanfare in the Lancet in 2019 and led to headlines such a ‘Even one drink a day increases stroke risk, study finds’ (BBC).

It may be a failing on my part, but I have never understood how “genotype-predicted mean alcohol intake” can be calculated. I can see how some people have genes that make them more or less likely to drink moderately, heavily or not at all, but I don’t see how this knowledge helps us estimate their alcohol consumption to the nearest unit per day (as some of these studies claim to be able to do). Clarity for the layperson is not always prioritised by the authors of MR studies and so, as with everything in this post, let me know in the comments if I am missing something.

It seems to me patently unsatisfactory to extrapolate any lessons about moderate drinking from a population that has unusual genes that make any amount of drinking unpleasant and more risky than it is to people in the rest of the world. The fact that there is no gene for moderate drinking means that MR will never be a suitable way of testing the hypothesis and no amount of hype about MR’s ability to “prove” causality is going to change that. Indeed, some critics of MR have cited studies of alcohol consumption as specific examples of overreach.

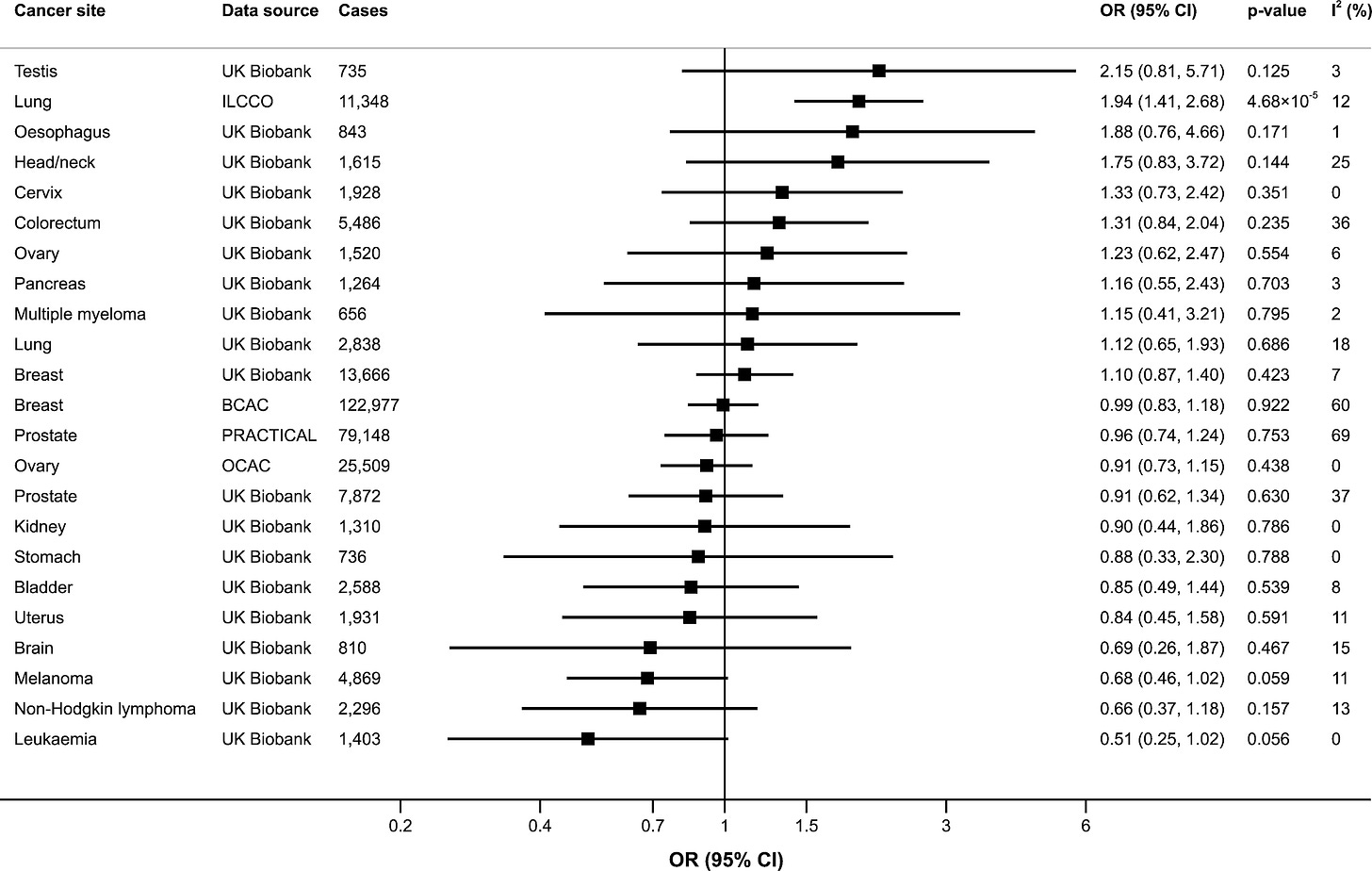

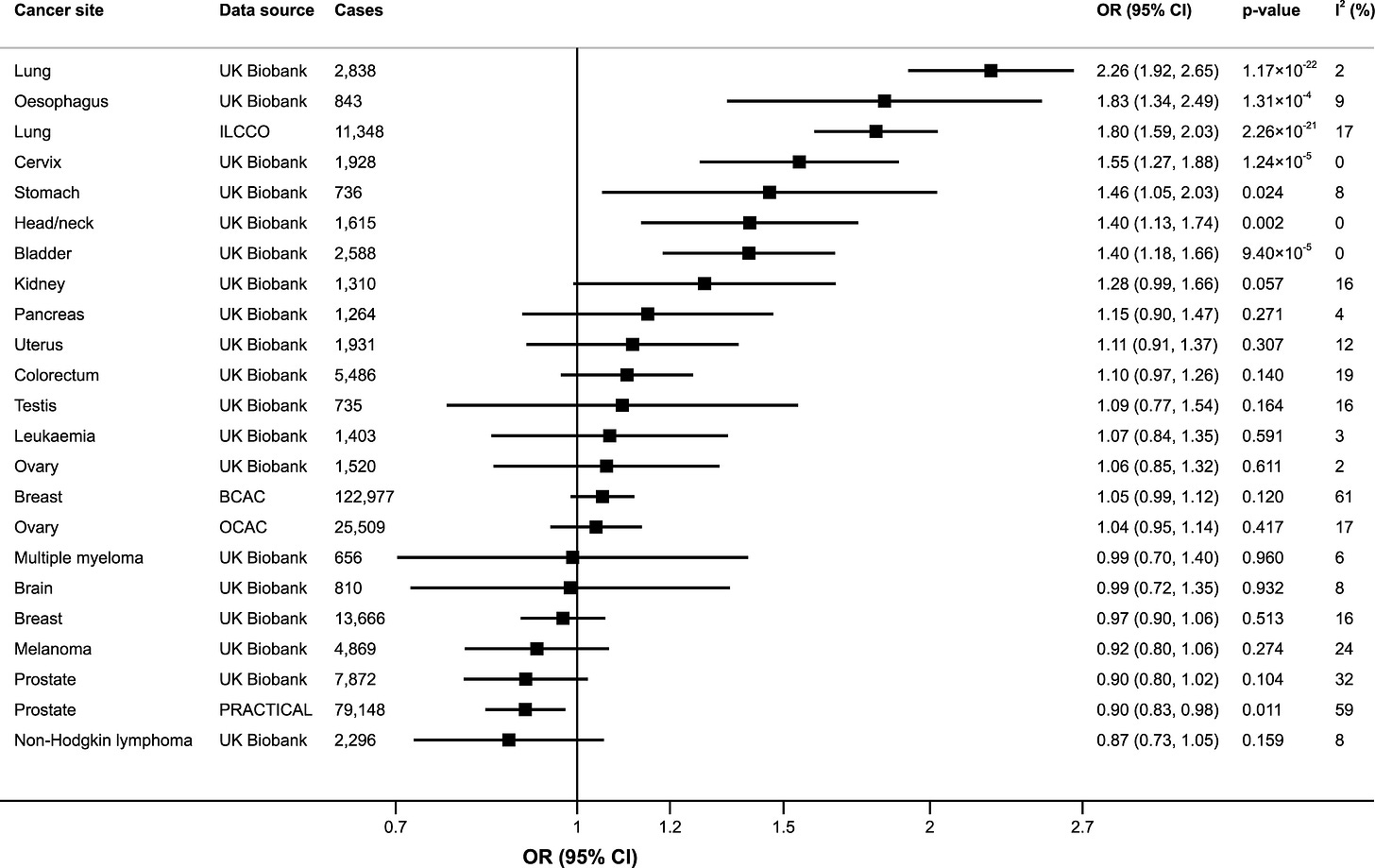

A more modest but reasonable role for MR is in looking at whether drinking in general causes various diseases. That simply requires a gene (or genes) that predispose people to drinking (or not drinking). We can then look at these people in the aggregate and study their health outcomes. However, when this has been done, the results have been less useful than conventional epidemiology. Although the ‘public health’ lobby insists that alcohol consumption causes breast cancer, even at low levels, MR studies have consistently failed to find any such association. And while we are told that alcohol consumption causes at least seven forms of cancer, an MR study published in 2020 didn’t find a statistically significant association with any of them. The only statistically significant association it found was with lung cancer, which suggests that the genes they were looking at were a better predictor of smoking than they are of drinking (or heavy drinking, at least). By contrast, another MR study found that “habitual consumption of alcohol with meals” dramatically reduces the risk of lung cancer.

Speaking of smokers, the same study found an association between a genetic disposition to smoke and lung cancer - and several other cancers - but the relative risks were small and suggested that smokers were only twice as likely to get lung cancer than non-smokers. Decades of epidemiology (and other evidence) strongly indicates that they are actually 10-50 times more likely to get lung cancer.

The obvious problem with using MR to study the effects of lifestyle choices is that they are choices. A genetic tendency to do something does not mean that you will do it, especially if there are strong economic and social pressures pushing you in the other direction. The benefit of MR studies is that they can, in principle, cut through confounding factors. They can also, in theory, get rid of the problem of recall bias (some people say they don’t smoke when they do and some people forget or lie about how much they drink). If there were a 1:1 relationship between the gene and the behaviour - if having the drinking gene guaranteed that you drank - MR would be very useful indeed, but there isn’t, so all it does is create a much bigger misclassification problem than you get in observational epidemiology. You don’t just get a few smokers misclassified as non-smokers or a few drinkers misclassified as teetotallers. You get loads of them. As a result, only the very strongest associations from epidemiology - like smoking causing lung cancer - are visible in the fog.

This is all by way of an introduction to a new MR study published this month titled ‘Effects of alcohol consumption on employment and social outcomes: a Mendelian randomisation study’. It concludes:

Alcohol consumption may increase the risk of living in deprived neighbourhoods.

That is a strange way of putting it. Wouldn’t it make at least as much sense to say that living in deprived neighbourhoods increases the “risk” of alcohol consumption?

It also concludes that alcohol consumption…

… may have deleterious effects on employment (including unemployment) and income, but these differ strongly by sex, largely affecting men.

These findings are somewhat surprising as it is widely agreed that people on low incomes drink less than people on high incomes on average (hence the alcohol harm paradox). Heavy drinking is associated with unemployment but that seems to be because people drink more when they’re unemployed rather than heavy drinking making them lose their jobs.

The societal cost of alcohol would be higher if it could be shown that drinking has a negative effect on people’s incomes and job prospects. I suspect that is why this particular MR study was conducted. All benefits associated with drinking must be erased. If so, the authors got the findings they wanted. But, in practice, the study is further evidence that the MR approach to this issue is worse than useless.

The authors get their associations between genes and alcohol consumption from this study. The science is beyond me so I will take it on trust but, as an aside, it is worth noting one of its findings…

Smoking phenotypes were positively genetically correlated with many health conditions, whereas alcohol use was negatively correlated with these conditions, such that increased genetic risk for alcohol use is associated with lower disease risk.

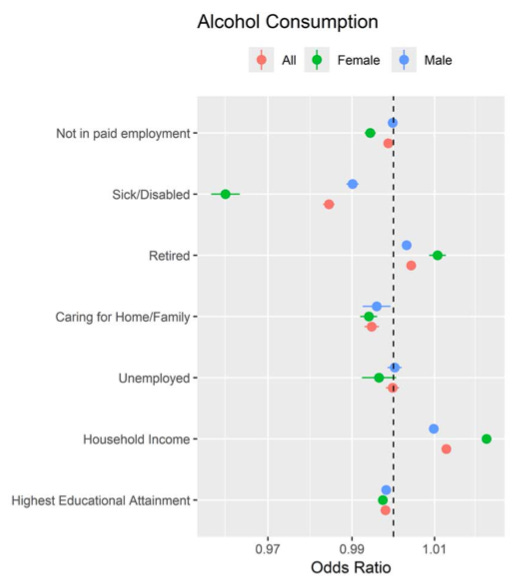

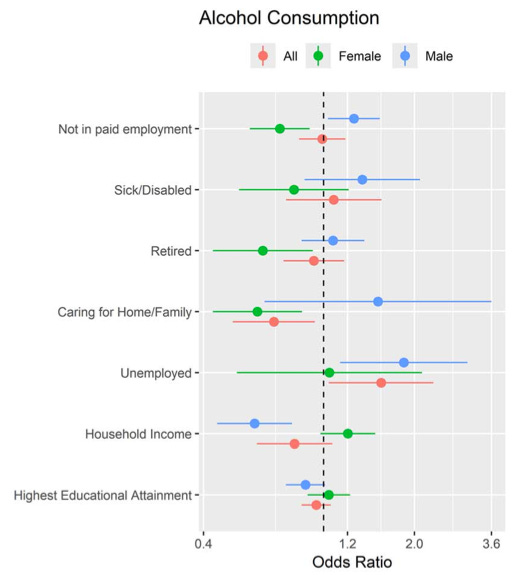

But the health effects of drinking are not what this MR study is about. The authors ran two analyses. The first used conventional epidemiology, i.e. surveys asking people how much they drank. It produced results that are not terribly surprising. Drinkers were less likely to be sick or disabled (especially women), slightly less likely to be carers, more likely to be on a high income and slightly more likely to be retired. In most instances, we’re talking a percentage point or two either way.

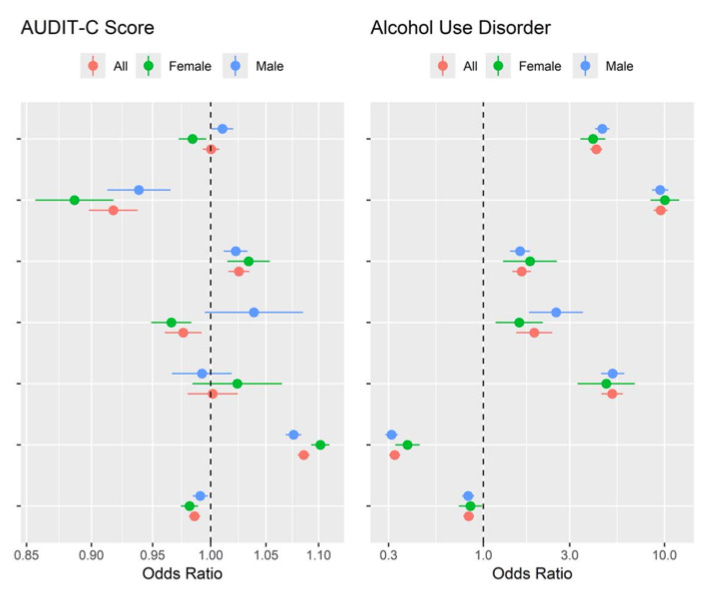

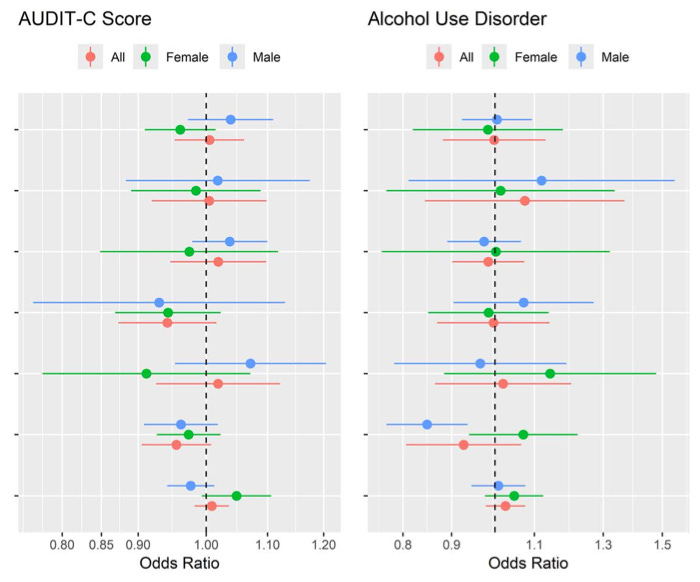

If you look at people who drink heavily, the picture is different. Firstly, note that the x-axis is suddenly much broader. People with an alcohol use disorder2 are much more likely to be unemployed and sick/disabled. They also have a much lower income. Again, this is unsurprising.

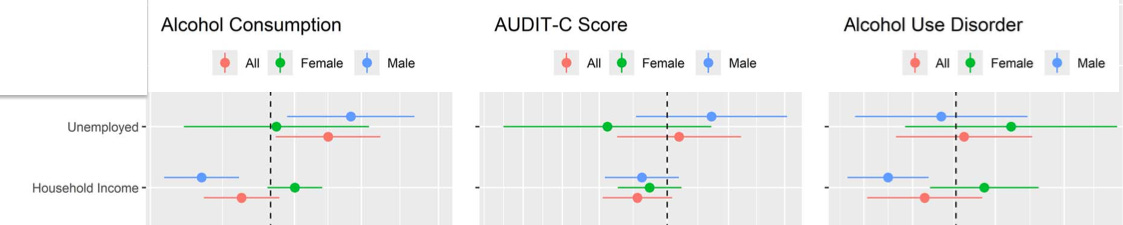

Now look at the results from the MR analysis which uses genetics to predict how much the same people drink. The female drinkers are still less likely to be unemployed but the men are now more likely to be unemployed. Female drinkers are now less likely to be retired than both non-drinkers and men who drink (the reverse was true for both before) and the men - but not the women - now have a lower income. And this time the effects are quite large (again, note the x-axis).

If that all seems a bit weird, wait until to see the heavy and dependent drinkers. In the MR analysis, people with alcohol use disorder don’t have higher rates of unemployment and only the men have lower incomes.

According to this study, men are more likely to have a job if they’re alcoholics than if they’re moderate drinkers.3 This doesn’t seem very likely. And while conventional epidemiology suggests that people with alcohol use disorder are ten times more likely to be sick or disabled than non-drinkers, the MR analysis suggests that they are only 7% more likely - and even that is statistically insignificant. Trebles all round!

None of this passes the smell test, but the authors soldier on. In the discussion section, they acknowledge that the dramatic differences in outcomes between men and women do not have a lot of support in the rest of the scientific literature (to put it mildly), but they barely mention the apparent protective effects of alcoholism, nor other anomalies, such as drinkers being less likely to be retired when MR is used to guess predict whether they drink but are more likely to be retired if you simply ask them whether they drink. And what is all that about anyway? Being retired isn’t a consequence of drinking. It is just a characteristic of some of the people in the study. Are we supposed to believe that there is some strange confounding factor that has led conventional epidemiologists to misclassify the retirement status of drinkers for all these years?

It doesn’t make sense to me, but they’ve got the result they want, namely that…

Our MR analyses support alcohol consumption having considerable adverse economic impact by increasing deprivation. It also indicated deleterious effects of alcohol on employment.

The results actually show no statistically significant association between (genetically predicted) drinking and income for both sexes combined. What it shows is lower incomes among male drinkers. Females are fine, even if they’re alcoholics, apparently.

Also in the conclusion, they say:

As drinking behaviour is modifiable there is potential for substantial reduction in alcohol’s health, social, and economic costs through public health initiatives.

If drinking behaviour is modifiable - which it is - how can you tell how much people are drinking by looking at their genetic make up? That is the fundamental problem I have with these MR studies. They can only provide reliable evidence if you take a highly deterministic view of human behaviour and assume that people are destined to live a certain lifestyle because of their genes. But the whole point of “public health” lifestyle regulation is to change people’s behaviour. If those policies get people who are genetically predisposed to drink to stop drinking, MR studies in the future will be even wronger.

Caution should be exercised when generalising these results across societies and time.

Good advice.

Or drinking in general. As an evidence review noted last year: “MR studies on the effect of alcohol on health are hampered by the lack of specific polymorphisms specifically addressing alcohol use.”

“Participant alcohol use disorder (AUD) status was based on self-report and hospital inpatient diagnosis. The subject was positive for AUD if they: (i) self-reported alcohol dependency or alcoholic liver disease/alcoholic cirrhosis (UKB field 20002), (ii) had a main or secondary ICD10 diagnosis of F10.1 or F10.2, or (iii) had a main or secondary ICD9 diagnosis of 303.9, 305.0, 305.1 or 305.9”.

There are no specific results for moderate drinkers, but since drinkers in general have a higher risk of unemployment than heavy drinkers - according to this study - it stands to reason that moderate drinkers must also have a higher risk.

I agree with your analysis. I would go even further and describe the studies you are summarizing as a total hot mess. It seems like a good example of the common problem of "epidemiologists" who can ape methods but really have no understanding of how to think scientifically. Or it could just be a calculated effort to get particular results for political reasons, as you suggest, which is certainly plausible.

The pretty-close-to-fatal flaw in using MR in this way is what I would tend to think of as confounding, though you describe it in terms of measurement error, which is also a valid way to think of it. (It is indeed technically measurement error (misclassification), but we tend to think of measurement error as close to random or in a particular direction because of one simple obvious cause. Whereas, confounding invokes complex webs of unacknowledged causal pathways like we see here.)

To take an example, imagine that there really were a gene that predicted moderate drinking with a reasonable degree of accuracy (that there really isn't is a fatal flaw of its own, of course). Using that, we no longer have the confounding from "what characteristics about someone's life and health would cause them to be a moderate drinker". But we introduce the seemingly much more complicated "give that someone is biologically predisposed to be a moderate drinker, what factors would make them not a moderate drinker (and in which direction)" and also "for those other people who are not biologically predisposed, what factors would make them a moderate drinker anyway". We can call these either confounders or causes of non-differential measurement error that could easily be associated with the outcome of interest. Whatever you call it, this is pretty obviously a far worse problem than any residual confounding from a proper study that uses actual reported behavior as the exposure.

This seems to be a case of someone reading that MR can help reduce confounding and having no understanding of how (and thus when) that is actually true. Or they are just pretending they don't understand.

Good insight. The problem with Mendelian randomization is the same as the problem with the use of Mendel's ideas a hundred years ago: it replaces human agency with genetic determinism. A hundred years ago this was a central feature of eugenics, which sought to replace the exigencies of things like poverty and other features of what we now call social determinants of health with some genetic predisposition. Is it not surprising then that the neo temperance set (I like your term "temperance adjacent researchers" are beating the "corporate determinants of health" drum, thereby undermining discussion of key social factors that drive ill health: poverty, housing, education, etc.?