Now that Lucy Letby has been sentenced to a 15th whole life sentence and her appeal has been rejected, we are free to discuss the case for the first time since September 2023. Quite a few people believe that there may have been a miscarriage of justice, including some people whose opinion I respect. A New Yorker article that was banned in the UK when the case was sub judice sums up the case for the defence. I can understand why people have their doubts, but I think they are mistaken.

I should say from the off that I was not present at the trial and I have not read the court transcripts. I don’t pretend to know every detail of the case and I am not going to go down a rabbit hole for the sake of a convicted child murderer. I have, however, listened to about 30 hours of reporting by two journalists who were in court every day and who produced a detailed podcast about it (it was put out in real time so had to be studiously impartial for legal reasons). If I err in what I say below, feel free to let me know in the comments, but none of what I have to say requires a deep dive into the case.

It would be easy to dismiss scepticism about the verdicts as being due to people watching too many true crime documentaries on Netflix or finding it hard to believe that a young blonde woman with a cute name could carry out such acts. It is true that Letby ‘doesn’t seem the type’, but serial killers do not generally froth at the mouth. If they did, it would easier to catch them. There seemed nothing odd about Harold Shipman until he was found to have murdered 200 people. Peter Sutcliffe was living a dull suburban life with his wife when he killed and mutilated women in the north of England (the best explanation the psychologists could come up with for his behaviour was that he was a ‘mummy’s boy’). Nor was there anything outwardly odd about Beverley Allitt, whose case most resembles Letby’s. Serial killers who seem ordinary are more common than serial killers who seem deranged.

Even so, Letby did not just seem normal before she was arrested. Nothing uncovered since her arrest has suggested any mental illness, peculiar obsessions or bizarre behaviour. Shipman was a morphine addict. Sutcliffe had been caught with a hammer in 1969 and his best friend knew that he was fixated with prostitutes. Allitt has since been diagnosed with Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Letby had plenty of friends - some of whom maintain that she is innocent - and a loving family. She was neither shy nor an exhibitionist. Her mental health has deteriorated since she was arrested but no one is claiming that she is mad. She is the eternal normie, the ‘vanilla killer’. Among medics who kill their patients, she is - according to the criminologist David Wilson - an ‘outlier’. The prosecution did its best to find sinister meanings in her bland text messages, but none of them are inconsistent with her being a conscientious nurse who likes salsa and cocktails of an evening.

Moreover, there is a precedent for women being wrongly convicted of murder because of statistical fallacies. Sally Clark was sent to prison in 1999 for killing her children after a quite idiotic misuse of statistics by Roy Meadow. In a case that is often cited by Letby’s defenders, the Dutch nurse Lucia de Berk was convicted of multiple murders and attempted murders in 2003 because, according to the prosecution, it was simply too unlikely that an innocent person would have been present during all the deaths.

Tom Chivers has written a good article about this…

The Dutch paediatric nurse Lucia de Berk was convicted, in two trials in 2003 and 2004, of seven murders and three attempted murders of children under her care. A criminologist told her trial that “the probability of so many deaths occurring while de Berk was on duty was only one in 342 million”.

But even if that were the case — and again, it wasn’t; the RSS estimated that if you took into account all the relevant factors, the chance of seeing a cluster like that could be as high as one in 25 — that’s not the same as the chance that de Berk was innocent. In order to establish that, you would need to take into account the prior probability that someone would be a multiple murderer — a mercifully tiny chance. De Berk’s conviction was overturned in 2010, thanks in part to the work of Bayes-savvy statisticians.

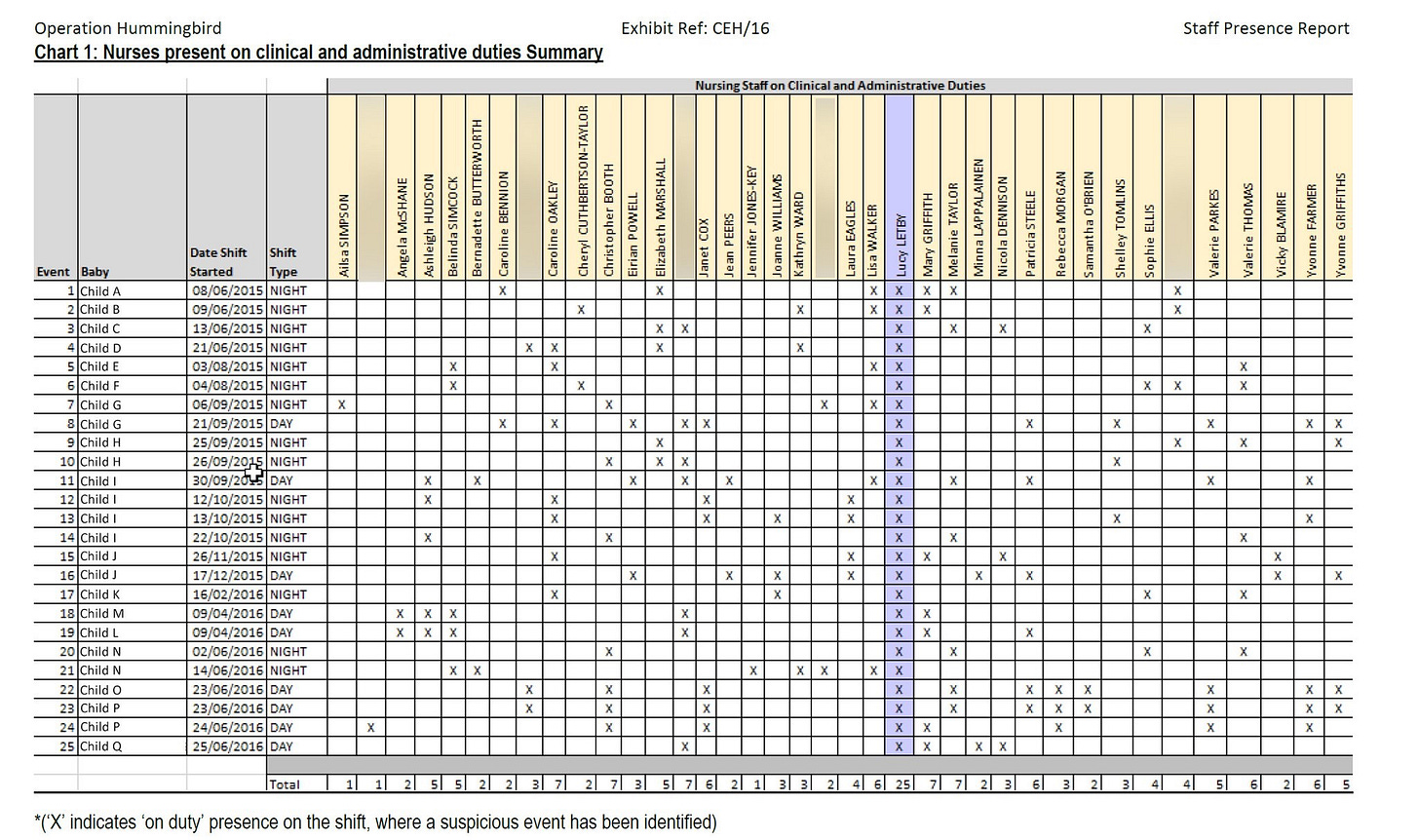

Put simply, the chances that any one individual will be caught up in a mass of coincidences is extremely small, but the chances that a mass of coincidences will occur somewhere in the world are quite high. Richard Gill, the statistician who helped overturn de Berk’s conviction, says he is ‘increasingly certain’ that Letby is innocent. So has Letby been the victim of a cluster of coincidences? Her defenders claim that she was convicted because she happened to be in the Countess of Chester hospital (COCH) whenever a murder or attack took place. The table below was shown to the jury as proof.

The sceptics claim that this is a case of the Texas Sharpshooter fallacy and that the police looked for every incident at which Letby was present, prosecuted her for those and ignored the rest. Letby thereby became the scapegoat for a rise in neonatal deaths in the hospital that could easily be explained by chance.

But that isn’t really what happened. Yes, the unusual rise in the number of deaths at the COCH between June 2015 and June 2016 does not prove that a serial killer was at large, let alone that it was Lucy Letby. But the police did not start with the conclusion that Letby was a murderer and work backwards. Instead, the staff at the COCH observed an extraordinary number of unexplained deaths and collapses and became increasingly suspicious of Letby. It was this suspicion that led one doctor to check up on her while she was alone with Baby K whom he found with her breathing tube dislodged and the alarm switched off while Letby stood idly by.

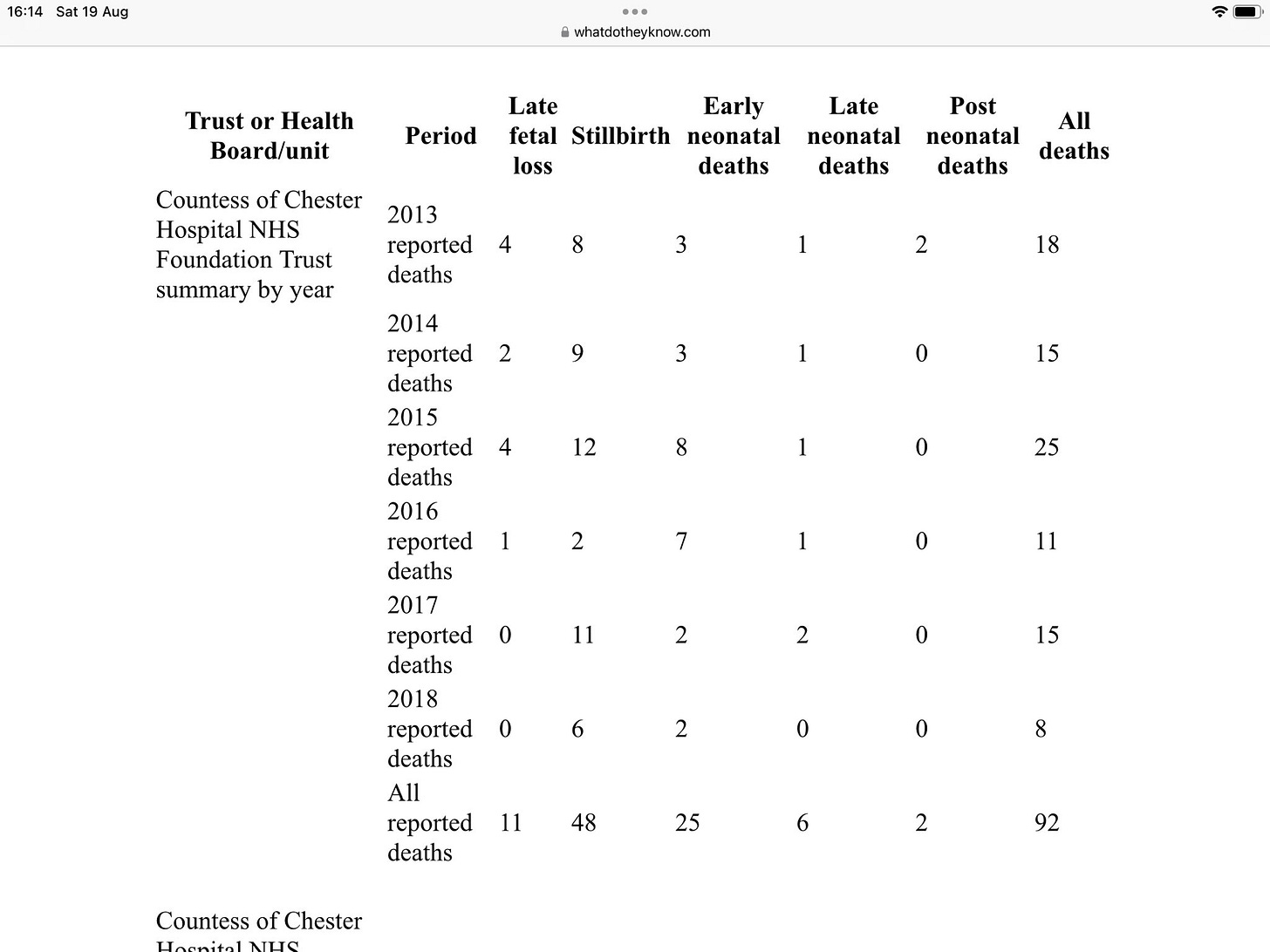

The babies taken in at the COCH were born prematurely - some of them very prematurely - but such is medical science that even very small babies usually survive. Unless they are born with a serious health condition, they just need to be fed and kept warm and they will grow until they are big enough to be discharged. It is unusual for a baby to be doing well and then suddenly die. Several babies doing well and suddenly dying is so unusual that it starts to look suspicious. There were only three early neonatal deaths a year at the COCH in the two years before Letby was working in intensive care at the hospital. In 2015, there were 8 (including 3 in June alone) and in 2016 there were 7. After Letby was suspended, the annual rate dropped to two.

Like so many things in this case, this could have been a coincidence, but for the doctors, it was not a question of mere numbers. Doctors know an unexplained death or collapse when they see it (and when the babies recovered from a collapse when Letby was around, the recovery itself tended to be unnaturally quick). They only went to the management about the suspicious deaths and collapses. They would have done it sooner but there needed to be a large number of unexplained incidents before they could think the unthinkable and conclude that one of their own was responsible. When the management finally went to the police, the police assigned a different detective to each case. Working independently of each other, they all developed suspicions about Lucy Letby.

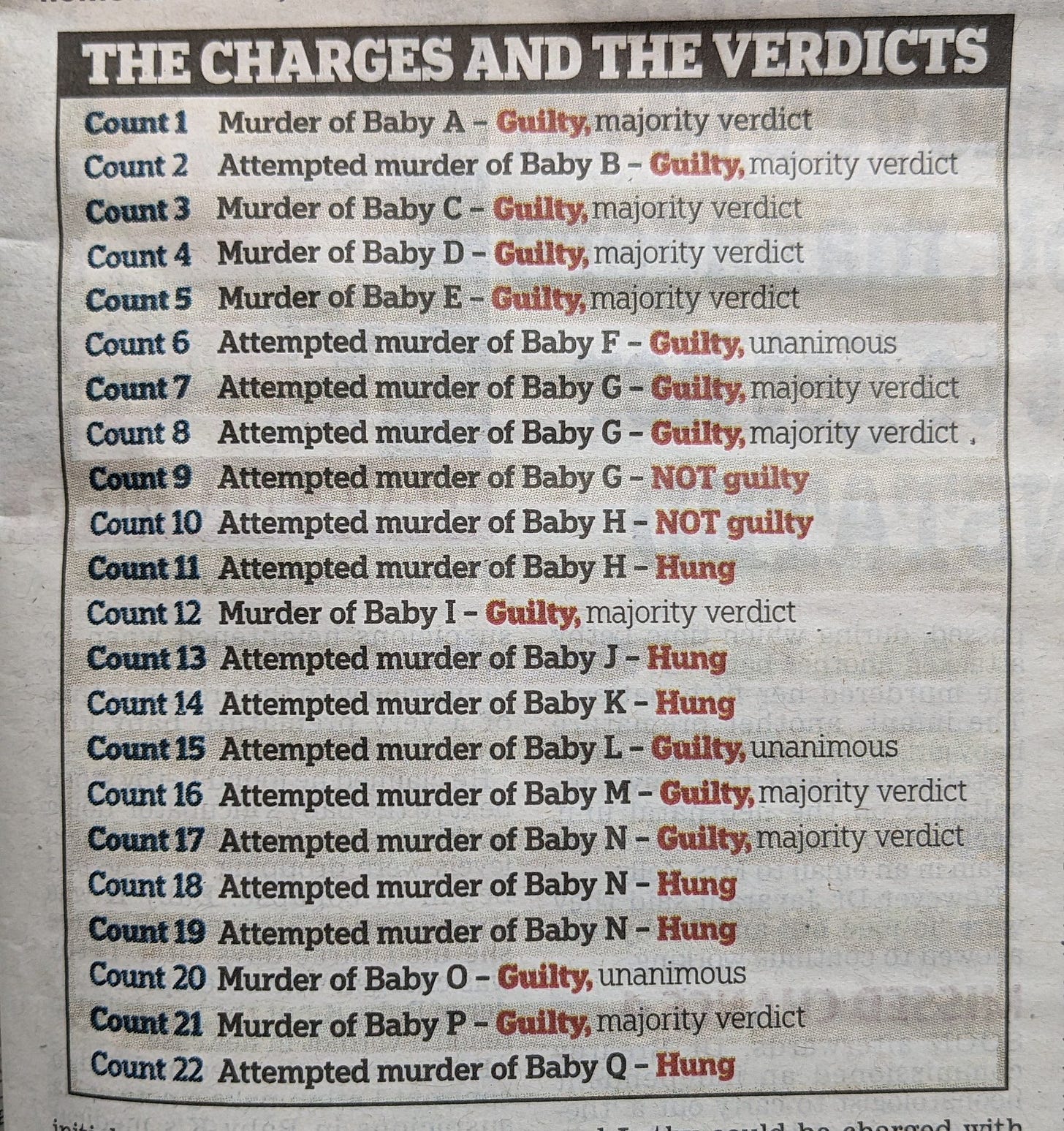

Letby’s trial was one of longest trials in British history. They obviously didn’t spend ten months talking about a spreadsheet. It was one piece of evidence among many and her lawyer, Ben Myers KC, is smart enough to have called it out as fallacious if there was any evidence of cherry-picking. The jury did not blindly assume that Letby must have been guilty of attacking a baby just because she was on duty when the incident occurred. She was found not guilty of two charges and failed to come to a verdict on six of them.

Why would Letby’s colleagues and the police try to frame her anyway? The conspiracy theory is that problems with the sewage system at the hospital caused a wave of infections that was responsible for the deaths and that NHS management threw Letby under the bus to avoid a scandal. Whether it was really less scandalous to have a serial killer wandering around the hospital for years is doubtful, but the fact of the matter is that NHS management at the COCH went out of its way to protect Letby. It was the doctors who wanted her off the ward and the management who forced the doctors to write a letter of apology to her. Far from throwing her under the bus, the management were desperate were keep the police away.

Staff and management at the COCH were extremely reluctant to believe that a colleague was harming babies and only came to that conclusion after the same thing kept happening again and again and again. The management did not want to bring in the police but eventually felt that they had no choice. The police themselves had no conceivable reason to frame her.

It is fair to say that the coincidence of Letby being present whenever a suspicious incident occurred is what led to her colleagues becoming uneasy about her presence in the hospital, but this took place in real time. They did not retrospectively define incidents as suspicious to fit the theory that she was a killer.

In any case, the evidence from the staff rotas is stronger than the sceptics suggest. Not only does it show that Letby was the only member of staff present at all the incidents, but it also showed that ‘many of the earlier incidents occurred overnight, but when Letby was put onto day shifts, the collapses and deaths began occurring in the day’. And if you accept that somebody was attacking babies at the COCH, the fact that Letby was the only one present at all the incidents becomes a very salient point. Some sceptics think that the deaths were all from natural causes but even Letby admitted that somebody was killing children in the hospital. It was conceded by the defence that the cases of insulin poisoning must have been deliberate. If it was not Letby, then who was it?

Letby’s presence during all the incidents is a necessary but not sufficient condition to find her guilty. The rest of the evidence came from eye witness accounts, the confessional Post-It note, text messages and, above all, medical records. For the latter, you have to go through each case one at a time looking at the circumstances, spotting the patterns and coming up with explanations. Some of them are stronger than others. A few of the charges are so flimsy they would never have been made if they hadn’t been part of a package (as noted, the jury did not convict on eight counts). Others might have stood up individually. But it is what they amount to when taken together that really counts. Detailed case-by-case accounts are impossible to summarise in a blog post, but it is what the jury spent months listening to and they concluded that Letby was responsible for most of the murders and attempted murders. There simply seemed to be no other plausible explanation for what happened.

All the evidence is, as the sceptics complain, circumstantial to a greater or lesser extent but that is not unusual in a criminal trial. When I was on a jury a few years ago, the evidence was almost exclusively of the he-said, she-said variety. Taken individually, each charge could have been dismissed on the basis that the victim was lying or confused or whatever. The jury convicted because there were consistent patterns of behaviour reported by people who did not know each other, who lived in different parts of the country and who seemed credible. Strictly speaking, it was possible that several different people decided to lie about the same man doing similar things over a period of 20 years, but in the absence of any plausible motive for them to do so, the defendant’s guilt had to be considered beyond reasonable doubt.

Lucy Letby was convicted not because she was present during every suspicious death or because she changed the hospital records or because she Googled the parents of the babies who had died or because she wrote ‘I am evil I did this’ and ‘I killed them on purpose’ on a Post-It note or because she was caught standing passively in front of a dying baby or because she hoarded handover sheets at home or because so many of her her colleagues became convinced that she was a serial killer or because the unexplained deaths and collapses ceased when she left. She was convicted because of all of these things combined (and more).

You may still disagree with the verdict - I wouldn’t have liked being on the jury myself - but that was the case. It did not come down to a single spreadsheet.

Other posts on this subject:

Further thoughts on Lucy Letby

“even Letby admitted that somebody was killing children in the COCH hospital.”

This is not the full story.

She and her Defence team were told pre-trial that experts had confirmed that tests had proved 2 babies were deliberately poisoned with insulin. However, the tests used do not prove poisoning. Prof Vincent Marks who helped convict Allitt stated that using the tests alone without physical evidence such as contaminated equipment or additional analysis of the blood samples risked miscarriages of justice.

Prosecutor Johnson used Letby’s acceptance against her during her cross- examination, but it was based upon Letby being provided misleading and incomplete evidence!

“Why would Letby’s colleagues and the police try to frame her anyway?”

“Frame” is not what is being claimed

The consultants and lead expert convinced the Cheshire Police she was guilty early on and from that point the Police worked on the presumption of guilt and viewed all the information they obtained to support guilt. There is no doubt they think she is guilty, although their confidence will have been dented by the Child K Retrial.

For the consultants, because the alternative explanation is a combination of factors relating to prematurity, but also inadequate care at the Unit and the fact that Lucy Letby won a grievance after complaining about their treatment of her.

Like the Post Office it is a train that no one was able to stop.