No, Liz Truss did not cost the UK £74 billion

And the government didn't spend £37 billion on an app

Last autumn, there was a popular myth that the Truss/Kwarteng mini-budget had blown a £30 billion hole in the economy. As I explained in a previous post, this was based on a misreading of an inaccurate graph from the Resolution Foundation.

This figure has since been inflated to £74 billion and joins the £37 billion supposedly wasted on ‘track and trace’ as a prime example of Tory profligacy. £111 billion is a lot of money and you will often find unintelligent Twitter users claiming that if the government can find £111 billion for ‘an app that didn’t work’ and a ‘disastrous mini-budget’, it should able to find billions of pounds for whatever it is they want to spend money spent on, usually ‘our NHS’.

The £74 billion claim is usually confined to angry replies to Conservative politician’s tweets but it was spotted live on TV this week coming from the mouth of someone I don’t recognise but whom I assume is a trade unionist.

The only source I have seen cited for the £74 billion figure is a short Daily Express article from 26 October 2022 titled ‘Kwasi Kwarteng's budget blunder cost UK an eye-watering £74billion, finance chief reveals’. The Express is not usually considered the newspaper of record by the kind of people who still have #JohnsonOut in their Twitter bios, but it has to suffice because no other media outlet reported this. The reason no other media outlet reported it is that it’s bollocks.

The article quotes the head of the UK's Debt Management Office, Robert Stheeman, speaking to the Treasury Committee. This is the relevant sentence:

He said that the office’s overall financing requirement increased from just over £160billion to £234billion, which he admitted was “not an insubstantial amount”.

That does indeed amount to £74 billion and is similar to the borrowing expectations in the Truss/Kwarteng’s ill-fated ‘Growth Plan’.

1.12. The government has announced a significant policy package that will reduce the pressure on households and businesses across the UK from rising energy bills. External forecasters expect this support for households to lower CPI inflation by around 5 percentage points this winter. The package will lead to additional borrowing, but by cushioning real incomes and protecting viable businesses it will support GDP growth in the near term, reducing the risk of the UK economy entering a deep and damaging recession which could weaken the fiscal position, by leading to elevated borrowing. This package in turn lays the foundations for long-run growth. Lowering inflation in the near term will reduce debt servicing costs, while boosting economic activity which will create an indirect fiscal benefit through higher tax receipts.

1.13. To fund the cost of this package, the Debt Management Office Net Financing Requirement (NFR) in 2022-23 has been revised upwards, from £161.7 billion in April 2022 to £234.1 billion in September 2022. This will be financed by additional gilt sales of £62.4 billion and net Treasury bill sales for debt management purposes of £10.0 billion, relative to April.

That’s an increase of £72.4 billion. Close enough.

But there’s a very important point to bear in mind about The Growth Plan. It never happened. Almost every part of it was reversed before it could come into effect. The expectation was that it would require around £74 billion of extra borrowing, but £74 billion was never borrowed because the plan did not come into effect. What the Debt Management Office put aside in October is not necessarily what it spent.

Having said that, the most expensive part of the mini-budget was kept. The Energy Price Guarantee will remain in place until at least April. Last autumn, there were fears that capping everyone’s gas and electricity prices could cost as much as £70 billion a year, but that was based on a worst case scenario from Cornwall Insight and never looked likely. The full cost will be significantly less than that and the amount the government will need to borrow will therefore be lower.

The other part of the mini-budget that survived was the scrapping of the Health and Social Care Levy which, in effect, would have been a 1.25% increase in National Insurance. According to the government’s estimate in September, this will cost the Treasury £17 billion in 2023/24. That is not a cost to the taxpayer. It is more like a saving to the taxpayer, at least in the short term. Eventually the money will have to be paid back (or, more likely, inflated away) so, in practice, it is neither a saving nor a cost. It is a transfer.

If you want to argue that the government shouldn’t be protecting anyone from the full cost of the global rise in energy prices and should instead be taxing them more, be my guest. It’s not my view, nor is it the view of the Labour Party which consistently voted against the Health and Social Care Levy and wanted an even more generous energy price cap.

These policies have certainly required more borrowing, although less than £74 billion, but let’s be honest about where the money has gone. It was not spent on ‘rich elites’…

It did not ‘cost the country’ anything, per se…

And the money was not ‘burned’…

It was, in fact, spent on the only two Truss policies that had widespread and cross-party support.

The only plausible costs that can be associated with the mini-budget are those which arose from markets worrying that the UK would never balance its books.

Firstly, there was a week or two when the pound fell against the dollar. It’s difficult to quantify what the economic cost of this was, if any, but it soon recovered.

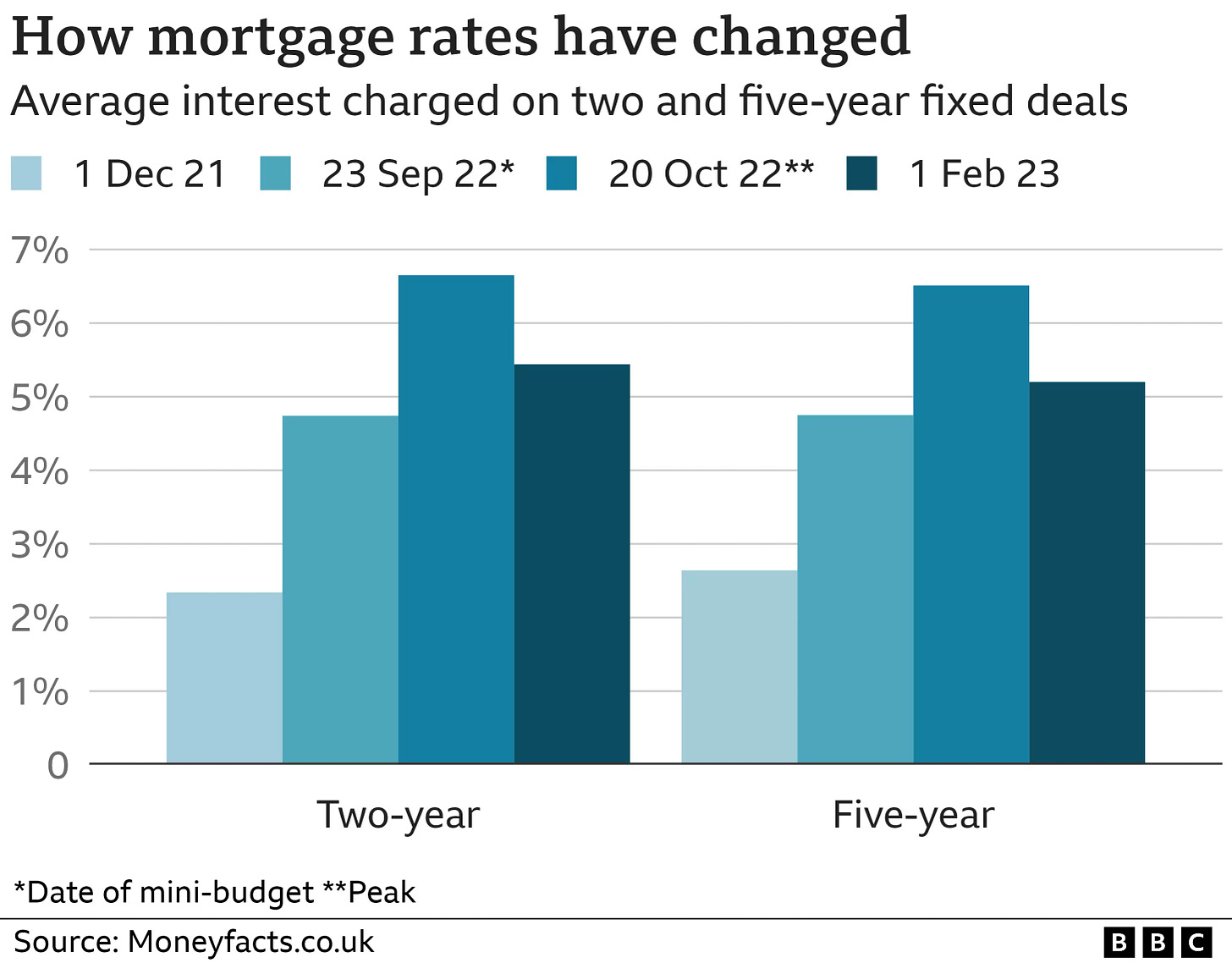

Secondly, mortgage rates rose in anticipation of higher interest rates. One of the problems with the mini-budget, as I said at the time, was that cutting taxes and going to for growth was likely to be inflationary (and thus require higher interest rates). But it cannot be said too often that the mini-budget didn’t happen. Interest rates have been gradually increasing in line with pre-Truss expectations, mortgage rates have fallen to where they would have been without the mini-budget, and it is difficult to argue that there has been any lasting effect.

Thirdly, as was widely reported at the time, the Bank of England put aside £65 billion to buy gilts to save the pension industry from its reckless gambling. Less widely reported was the fact that it only spent £19 billion of this and it subsequently made a tidy profit of £3.8 billion when it sold them.

As a fiscal conservative, I welcome anyone who suddenly became concerned about the deficit last September. Better late than never. But even I would not portray the government borrowing money to cushion people from exceptionally high prices as ‘blowing a hole in the economy’ or as a waste of cash. It was not a deadweight cost. The money didn’t disappear. And it wasn’t £74 billion.

So overall £3.8Bn up! Well done everybody :)

It is clear that the political uncertainty of the Truss interregnum has had costs outside of those directly incurred by government legislation (which she didn't have time to pass any of). Markets do not react kindly to instability, and they don't react respond well to leaders with unconventional economics.

Since you are on the political right Chris, here's a hypothetical example that might better align with you priors. Imagine that in 2017 Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party had finished with just a couple extra percent of the vote, enough to take his party into government. Ignore any legislation he seeks to enact. Even before he does that, the economy takes an immediate hit; as soon as the exit poll comes in investors lose confidence, sterling falls, there is noticeable capital flight, etc. Economic reality, and the fragility of his command of the House of Commons, force him to shed most of his radical plans (cf Francois Mitterand's "austerity turn"), but the damage has already been done.

You probably agree that the above scenario is a plausible what-if, so why is Liz Truss different? This isn't just a narrative, it's a real tangible effect of her six weeks of madness. Even though she's no longer PM, the market movers haven't forgotten and the chaos she instigated has left us with a new, permanently higher baseline of uncertainty.

It may be hard to put a figure on the true cost of this. No money was spent directly by the government, but it is clear that the UK economy is smaller for Truss's brief spell in charge. It may be hard to measure/calculate, but economists are able to put a financial value on just about everything. So has anyone done this work and come up with a believable number (including showing their working)?