The gene delusion

Mendelian Randomisation is running out of road in alcohol research

The “public health” lobby wants you to believe three things about alcohol.

It causes at least seven types of cancer.

Even light drinking increases the risk of breast cancer.

Moderate drinking does not reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke, dementia or premature mortality.

If you accept these premises, it leads to a fourth belief.

There is no safe level of alcohol consumption.

Evidence from observational epidemiology largely supports (1). There is flimsier evidence for (2) but it does exist. There is very little evidence for (3). On the contrary, the evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that moderate drinking has a protective effect. And if, as the epidemiology suggests, moderate drinkers live longer than teetotallers as a result of their moderate drinking, it makes no sense to claim that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption.

In recent years, studies using Mendelian Randomisation (MR) have challenged some of the epidemiological evidence. MR studies look at genes that are associated with certain behaviours, such as drinking, to see if they are associated with certain health outcomes. MR studies supposedly have the advantage of being able to cut through confounding variables and prove causation.

MR studies have generally failed to find a protective effect from moderate drinking on heart disease, and neo-temperance academics get very excited by this, but it comes with two big caveats:

Firstly, there is no gene for moderate drinking so researchers have had to use some highly dubious proxy measures instead.

Secondly, MR studies have failed to find associations between drinking and various health outcomes that we are pretty sure alcohol causes. An MR study in 2020, which I wrote about at the time, failed to find an association between alcohol consumption and any type of cancer, except lung cancer. No one seriously thinks that drinking causes lung cancer. It seems that the genes that supposedly predict alcohol consumption are actually better at predicting smoking. Using data from the International Lung Cancer Consortium, this study found a stronger link between drinking and lung cancer than it found between smoking and lung cancer!

The use of MR studies to detect lifestyle risks clearly has room for improvement. Last month, the authors of the 2020 study had another go at it. Their new study begins with the usual sales pitch about how MR beats observational epidemiology:

Observational epidemiological studies are limited in their ability to make reliable causal claims. It is well-known that “correlation is not causation”, and many causal claims based on observational associations have failed replication in randomized trials…

Mendelian randomization is an epidemiological approach developed to mitigate against bias from confounding and reverse causation that is pervasive in observational research.

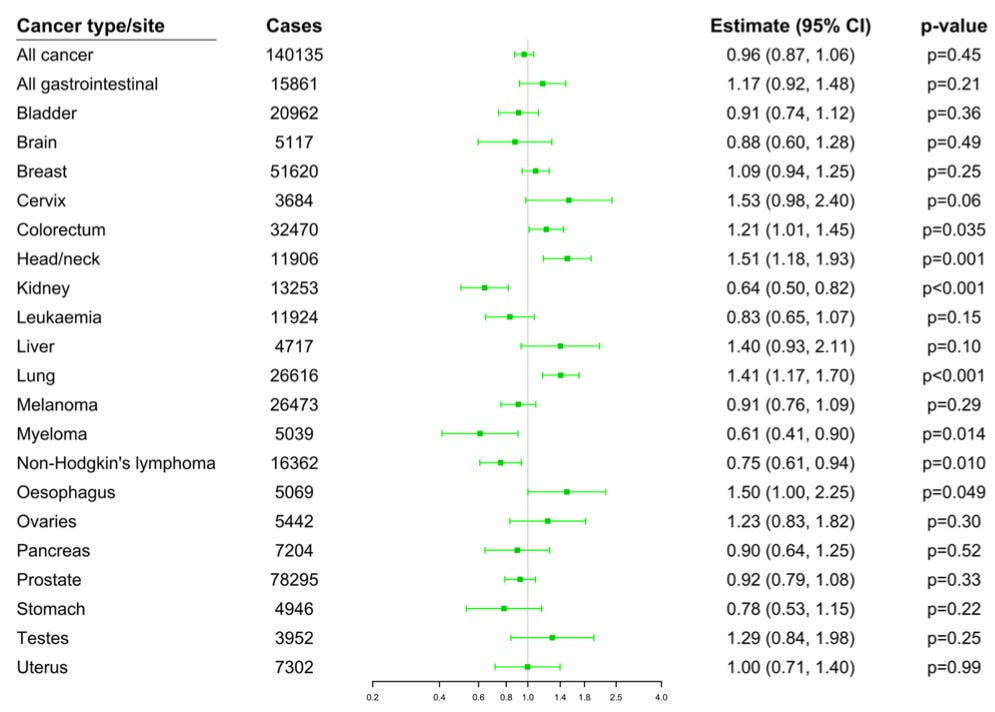

The authors used four large biobank datasets from the UK, Finland and the USA, looked at 95 genetic variants that are “associated with alcohol consumption” and looked at 20 types of cancer.

They found that genetically predicted alcohol consumption was associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer (OR 1.21), head/neck cancer (OR 1.51), lung cancer (OR 1.41) and oesophageal cancer (OR 1.50) although the associations were no longer statistically significant for lung cancer and oesophageal after the results were adjusted for smoking.

They also found that genetically predicted alcohol consumption was associated with a reduced risk of kidney cancer (OR 0.64), myeloma (OR 0.61), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (OR 0.75), stomach cancer (OR 0.59) and bladder cancer (OR 0.78). The association with myeloma was no longer significant after adjusting for smoking.

So that’s an increased risk of two cancers and a reduced risk of four cancers. Overall, there was no association between genetically predicted drinking and cancer (0.96 (95% CI 0.87, 1.06)). Although the authors don’t mention it in the text, genetically predicted drinking was actually associated with a statistically significant reduction in overall cancer risk after adjusting for smoking (OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.80-0.99)).

With regards to smoking, the authors say…

The positive associations of genetically-predicted alcohol consumption with cancer mortality, oesophageal cancer, and lung cancer attenuated, and became fully null for lung cancer, upon adjustment for smoking heaviness. A potential explanation for this finding is that alcohol consumption is culturally linked to cigarette smoking, such that alcohol drinking leads to an increased propensity to smoke. Hence, there may be an indirect causal effect of alcohol consumption on lung cancer, but smoking is the direct causal risk factor.

My own theory is that the genes that are associated with alcohol consumption are also associated with risk-taking, impulsiveness and addictive personalities, but that’s only a hunch. Either way, the fact that the results have to be adjusted for other variables rather undermines the claim that MR makes it possible to “mitigate against bias from confounding and reverse causation that is pervasive in observational research”.

Taken at face value, this study not only undermines the “no safe level” narrative but also undermines many epidemiological studies showing a link between alcohol consumption and several types of cancer.

There is suggestive evidence from observational studies that alcohol consumption may modestly increase the risk of melanoma as well as stomach, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. Our analyses and previous Mendelian randomization investigations do not support a harmful effect of alcohol consumption on these cancers.

Like every MR study that came before it, it failed to find an association with breast cancer:

The lack of association between alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in our Mendelian randomization analyses contrasts with meta-analyses of observational studies, which show a 5% to 10% increase in breast cancer risk per 10 g/day increment of alcohol consumption. This inconsistency may be due to residual confounding in observational studies.

And then there is the awkward fact that…

The strongest associations we observed were in the protective direction.

Observational epidemiology has also found a reduced risk of kidney cancer, non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma and myeloma among drinkers. This makes the authors believe that the effect is real.

Although we are generally sceptical about the value of observational research in making causal claims, the positive observational associations of alcohol consumption with most outcomes make these negative associations notable. We may expect bias from confounding to influence estimates for different cancer types in a consistent direction. Hence, we would interpret these observational associations as further evidential support that there might be a protective effect of alcohol consumption on these cancer types.

The authors are palpably unhappy with their findings, although it’s not clear whether they are more annoyed at their failure to find more health risks than at the failure of MR generally. Either way, it leads to a certain amount of cope in the discussion section, some of which smacks of desperation.

As we could only assess the diagnosis of cancer, it is possible that alcohol consumption increases the risk of undiagnosed cancer.

With a bit of snark aimed at their readers in the health community, they admit that the whole thing might be a waste of time…

There are many caveats and limitations to this research. Indeed, we tend to find that readers of our papers on Mendelian randomization are less sceptical about our findings than we are ourselves. Some limitations concern the genetic variants used in our analyses. The genetic variants may not be valid instrumental variables.

That would certainly explain it. Or…

Genetic variants may explain only a small proportion of variance in alcohol consumption.

This seems to be true. Elsewhere in the paper they say that…

In total, 95 variants associated with alcohol consumption were included in our analyses. The variants explained around 0.2% of the variability in alcohol consumption.

0.2%!

However, we want to leave readers in no doubt that alcohol consumption increases the risk of many diseases.

Just not many of the diseases you looked at.

It seems to me that MR research into alcohol is running out of road. Some of its findings have been literally unbelievable and MR researchers are not going to suddenly get different results unless they start making the kind of adjustments to the data that MR studies are not supposed to need.

Recall bias can be a problem in observational epidemiology but MR studies have replaced it with a much bigger misclassification problem. We simply don’t know whether someone with an alcohol gene actually drinks alcohol, let alone how much she drinks, and, as the issue with smoking in this study proves, there are still major problems with confounding factors.

It’s probably time to stop using MR in alcohol research. You could say that would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater, but it’s not much of a baby and the bathwater stinks.

Brillaint breakdown of why MR is hitting a wall here. The fact that these genetc variants explain barely 0.2% of drinking behavior is kinda wild when they're being used to overturn decades of epidemiological findings. I've seen similar issues with biomarker-based stratification in clinical trials where the proxy measure ends up capturing comorbidities rather than the exposure itself. When the smoking adjustment flips the lung cancer association, that's not confounding control, that's just proof the instrument is broken.

This whole discussion overlooks a fundamental fact... it's not the same thing to drink a shot of whiskey as it is to drink a shot of young (unaged) red wine rich in polyphenols and resveratrol.

Another very important point... it's one thing to drink a shot of alcohol in the company of friends, and another to drink alcohol due to stress or simply depression. It's very difficult to draw conclusions because it would be necessary to analyze not only the amount of alcohol consumed but also the context in which the drinker finds himself. There's certainly one factor not to be forgotten... alcohol is a diluent. It's been shown that alcoholics have reduced brain mass due to the direct action of alcohol on the brain mass rich in soluble fats, over the long period of chronic alcohol consumption.

Finally..., within our circulatory system there is a thin sheath called the endocalyx. This sheath protects small and large blood vessels and allows for greater blood flow. If this sheath is damaged, blood as it passes causes intravascular damage because a damaged or missing endocalyx sheath causes small cracks to form that are filled with calcium, fibrin, cholesterol, and other compounds that stiffen the blood vessel. Alcoholic substances not only burn glutadione (the liver burns its glutadione reserves to avoid damage). When glutadione is depleted due to excessive alcohol consumption, the liver inevitably suffers damage. Unfortunately, alcohol literally thins and then dissolves the endocalyx sheath. For this reason, drinking alcohol over a long period of time leads to an increase in blood pressure. This leads to a chain of events that leads to heart attack or stroke.

I personally drink a glass of young red wine (the best because it contains more polyphenols) a day. Even two. My theory is that we should grow old happily. Simple, right?

Andrew,

Greetings from Spain